Students from both Cal Poly Humboldt and UNIBE, Colectivo RevARK, and the neighborhood of La Yuca completed this project for the Escuela Basica Nurys Zarzuela in La Yuca, del Naco, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. The school was facing pressure to increase its size due to limited space and high enrollment. By building a new room at the school we could both increase the amount of space and explore the effectiveness of alternative building techniques.

Problem[edit | edit source]

The goal of this project was to explore cost-effective, environmentally appropriate alternatives to traditional building methods in the Dominican Republic while creating additional space for the Escuela Basica Nurys Zarzuela.

Criteria and Constraints[edit | edit source]

The following criteria were decided upon for this project. Criteria are weighted with "10" being of greatest importance and "1" being of least importance.

| Criteria | Weight | Constraints |

|---|---|---|

| Safety | 10 | Does not contain toxic chemicals that will cause harm to occupants. The structure is built to code and will not cause physical harm to occupants. |

| Durability | 9 | The structure will withstand the elements of Santo Dominingo. This includes potential earthquakes and hurricanes, humidity, high temperatures, and heavy rains. |

| Reproducability | 8 | The structure could be reproduced by local builders. |

| Cost | 8 | The project is less expensive to construct than traditional building styles. |

| Construction time | 8 | The structure can be completed before July 8. |

| Educational Value | 8 | The project instructs builders and occupants on the alternative building technique used in construction. |

| Reduction of carbon footprint | 7 | Materials should represent a lower carbon footprint than traditional building methoda. |

| Comfort | 6 | The structure is comfortable for occupants. Room temperature should be similar to that of other structures near the site. |

| Aesthetics | 5 | The structure is pleasing to look at. |

Literature Review[edit | edit source]

See /Literature Review for relevant research completed for this project.

Final Design[edit | edit source]

Community-Practivistas Dominicana Program Joint Decision[edit | edit source]

There were a few meetings prior to the beginning of the design process and design decision making. In these meetings, community involvement was essential. They had more knowledge relating to what was needed, where it was needed, and how problems could be solved. Having in mind that our focus was alternative building, we presented the community with some options. In class, we had learned about alternative building techniques, and presented the community with four of these potentially feasible options: wattle and daub, papercrete, rice and clay slip, or eco-brick (plastic bottle construction). The community and the building team of the Practivistas Dominicana Program came to a joint decision. This decision was based on our previously determined criteria, availability of materials, and community interests. All methods based on purely natural materials, or grown materials, like wattle and daub, bamboo and adobe were dismissed, because these materials are simply not available in the urban setting of the community. In the meeting, the conclusion was that the most accessible materials were plastic bottles and paper, and so it was decided that papercrete and eco-ladrillo construction were our best options.

Location[edit | edit source]

The building project was constructed in La Yuca del Naco, a small barrio located in Santo Domingo. It was built on the second floor, behind the classrooms of Escuela Basica Nurys Zarzuela primary school. The decision was based mostly upon where space was available, which was limited. Structural analysis proved the site would support a room if it were first reinforced.

-

The primary school

-

Second-story roof build site

-

Second story view from roof above

-

View of La Yuca from the top of the school

-

3D rendering of build site

-

3D rendering of school

-

3D rendering of aerial view of school

-

Sketch of build site dimensions: cross-section and aerial of 1st and 2nd floor

Prototypes[edit | edit source]

We constructed a number of prototypes/tests to get a feel for what would work best for our plastic bottle walls. Things we took into consideration were: how to orient the bottles, how to prevent bottle movement within the wire mesh, to fill or not to fill the bottles with trash, what mix of sand to cement to use for the plaster, and how to attach the wire mesh to the wood frame.

Papercrete Prototypes[edit | edit source]

For papercrete protoyping, we used several formulas that responded in different ways, according to the proportion of the materials used. The basic ingredients in the formula, which were mixed in different proportions according to the mix prepared, were:

- Soaked Paper (Newspaper)

- Portland Cement

- Sand

- Lime

Guided by our criteria, the formulas we prepared had to meet certain requirements:

- Cheap

- Safe

- Durable

- Easily Reproduced

Papercrete Brick Prototypes[edit | edit source]

General Conclusions[edit | edit source]

The first thing we found, is that the smaller, brick-sized prototypes were the easiest to make. This is mostly due to the amount of drying undergone by the bricks. Small bricks dry quicker, and therefore harden faster. Our first batch was tested at 4 weeks after they were taken out of their molds, and their performance proved to be very efficient when under compressive stress, but their tensile strength was rather disappointing. Although more tests should be made, we can infer, by observation, that drying is the biggest issue regarding tensile strength in papercrete blocks. Those that were drier performed better than those that were less dry.

Due to the long drying time of papercrete, and the fact that the whole program was only 6 weeks long, there was no use of papercrete in the actual construction. Although further research is needed, we can however conclude that papercrete could be a viable option in humid climates, given enough drying time. This time can be made considerably shorter if some critical steps are taken, some of which we tried under informal conditions. These are: compression of the blocks when poured into the forms, proper drainage (that is, designing a form that allows water to be shed more quickly), using pure sand and lime, that is without any clay in them, as clay is very hard to dry, and proper planning. If the weather is humid and rainy, blocks take longer and longer to dry.

From our research, the final conclusion is that the only disadvantageous factor in papercrete block-making is drying time, because the amount of moisture in our blocks is what determined how well they performed, both under compressive and tensile forces. From observation, we can conclude that drier bricks mean harder bricks, and hard bricks have both good tensile and compressive strength. Papercrete block-making could be planned for the dry season, and the bricks could even be dried indoors, in a warmer and drier environment. Further research would prove the efficiency of the technique.

Final Design Specifications[edit | edit source]

Walls: Conclusions based on the papercrete tests ruled out papercrete as a viable option for the span of our project. There simply would not be enough time to wait for papercrete to dry and complete the build process. Furthermore there was uncertainty about papercrete's performance in rainy, humid climates. We decided to build two walls out of plastic bottles, secured by 1cm metal screening, and plastered with traditional concrete plastering.For the third wall we would utilize the school's existing concrete block wall. The fourth wall was already partially complete, consisting of a 5'3" concrete block wall dividing the school and neighboring property. The rest of the wall would be filled in with reused styrofoam.

Columns: Since the walls themselves would not be able to support load, We decided to go with traditional concrete columns as the main support for our structure because of their strength, local knowledge available to help us build them, and their prevalence regionally in current construction makes them trusted by the community. With the help of local engineer José García and visiting engineer Tressie Blue we assessed the current school structure and decided on the placement and design of our columns. Two columns would be located on the second floor directly above the preexisting columns below them. A third column was to be located in the SW corner of the building. After assessment of the lower level, we found that there was currently no column in that corner of the school building, so we decided to create one that would be two stories tall beginning on the ground level. This would increase overall structural stability for the school and provide the load-bearing column needed for the ecoladrillo room.

Door Access: Prior to construction, access the site was difficult. The best way to add access to the future room would be to knock a hole into a small room adjacent to the build site.

Roof: The roof would be made of a wooden frame and corrugated zinc plates, as is the norm in the Dominican Republic. A number of things were taken into consideration when designing the roof, and a corrugated zinc roof was decided on for a number of reasons:

- Cost: aluzinc cost 5-10 times as much as zinc, and did not fit in our budget

- Weight: lacking columns on one side, a heavy concrete roof would need to be tied into the wall with rebar to be structurally sound. A zinc roof would be much lighter and could be supported easily by the adjacent roof and columns.

- Time constraints: A concrete roof would be much more labor-intensive and would take time for the concrete to set. A zinc roof could be constructed in half a day and fit into our time constraints much better.

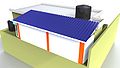

Below are the initial designs of the new storage room. The 3D render shows a rainwater catchment system. The gap on the right side of the 3D render was later changed due to structural constraints.

Construction Process[edit | edit source]

Process: Building Columns[edit | edit source]

The first step we took in the on-site construction process was to build the columns. To secure them to the existing structure, we drilled holes 20cm down into the existing columns, and then pounded rebar into them. These pieces of rebar stuck approximately 45cm above ground and were then secured to the rebar frame of the column with wire ties (Fig 4).

The big column: The third column would take slightly more work In order to achieve a higher level of strength we chiseled a hole in the roof (Fig 3) where the column was to be placed so that we could lower down an entire two story tall rebar column frame without having to cut it in half.

Securing the big column: After much consideration it was decided that to secure the big column we would drill 20cm into the floor of the first level, and sink the rebar in there. However, after we began drilling we found that after only 8cm there was a pocket of airspace beneath the cement floor. This would not provide enough stability to for our column. Luckily there were two back up plans. One was to build a concrete footing above the ground (0.8m x 0.8m x 0.6m with a mesh work of short rebar pieces placed into the middle). The second idea was to drill holes on both sides of the wall at every 40cm interval that corresponded with the rebar rings on the frame of the column. These holes would be drilled at different angles into the wall and a 20cm piece of rebar would be placed in them, leaving 10cm in the wall and 10cm sticking out. The piece sticking out would be wired to the column frame. In the end, we chose option number two.

Attachment points for chicken wire: To create strong connection points for the chicken wire (which eventually creates the walls by holding in the bottles), we placed wire sticking out of the columns. To do this, we drilled 1/4" holes in the forms where we wanted the wires to attach. After pouring concrete, we simply bent short pieces of wire in half and inserted them into the holes. As the concrete hardened it secured the wire attachment points. The wires were spaced every 20cm running up and down the column along two lines, 8cm apart (Fig 8). We chose the 8cm spacing because it was the size of our largest diameter bottle, and we wanted the chicken wire to fit snugly. This method actually turned out well, and we were able to attach the chicken wire easily and pull it relatively tight. We also used two different gauges for the wire connection points, which yielded differing opinions as to which was more effective. The thinner gauged wire was easier to manipulate yet required more tying to ensure a solid connection.

-

Fig 1: Tie ribs with metal wire.

-

Fig 2: Place ribs every 20cm.

-

Fig 3: Make holes for the rebar, 20cm+ deep.

-

Fig 4: Pound in rebar, tie in rebar for columns.

-

Fig 5:

-

Fig 6: Make forms.

-

Fig 7: Place forms around the rebar and pour cement.

-

Fig 8: Remove forms after 24 hours.

Column Materials & Budget[edit | edit source]

| Materials | Unit Price (RD$) | Quantity | Total (RD$) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Portland Cement | $267/ft^3 | 4 | $1068.00 |

| Gravel and sand mixture | Donated | 12 ft^3 | $0.00 |

| 10g Metal Wire | 36.21/lb | 3 lb | $108.63 |

| 2" Wood Nails | $28/lb | 2 lb | $56.00 |

| 4'/8' Plywood Board | $1100 | 2 | $2200.00 |

| Rebar 3/8" by 20' | 154.75 | 8 | $1238.00 |

| Rebar Rings/Ribbing | 18.10 | 32 | $579.20 |

| Total Cost | $5249.83 | ||

Process: Building Roof Supports and Attaching Roof[edit | edit source]

-

Fig 1: Making the columns the correct height.

-

Fig 2: Using a metal pipe and arm power to bend the rebar over the wood frame, as to secure it firmly.

-

Fig 3: Notching cut into roof frame to enhance stability.

-

Fig 4: Rebar bent over to secure frame to columns.

-

Fig 5: Rebar from the column is threaded through holes drilled in the wood.

-

Fig 6: Holes were drilled along the pre-existing school roof and the wood framing for the roof. Rebar was pounded through the wood and into the hole in the concrete below. Finally rebar bent over to secure frame to roof.

-

Fig 7: Roof framing continues.

-

Fig 8: Broader view of roofing process.

-

Fig 1: Installing the roof.

-

Fig 2: Finishing installation.

Roofing Materials & Budget[edit | edit source]

| Materials | Unit Price (RD$) | Quantity | Total (RD$) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3'x6' Corrugated Zinc Panels | $270 | 14 | $3780.00 |

| 2x4, Pine | |||

| 1x4, Pine | |||

| 4" Wood Nails | $45/lb | 2 lb | $90.00 |

| 20 ft, 4" PVC | $343.09 | 1.5 | $515.97 |

| Rebar | Scrap,Donated | 9 | $0.00 |

| 2" Zinc Roofing Nails | $39.90/lb | 2 lb | $79.80 |

| Total Cost | $4465.77 | ||

Process: Building Bottle Walls[edit | edit source]

Plastic bottles: As identified by the community as a resource, and as observed by our team, plastic bottles are abundant on the streets of Santo Domingo. In the beginning of the process we estimated that it would take about 1800 plastic bottles to complete our project. We obtained our bottles through a mixture of hunting bottles in the streets with 30-55gal plastic bags, locating signs and collection boxes at UNIBE and local colmados, and donations from La Yuca residents. When hunting for bottles we recommend looking in places where people tend to congregate. For example, in a matter of 1 hour, three people were able to collect approximately 500 bottles in a bottle-rich area called the Malecón in Zona Colonial, Santo Domingo.

Bottle recommendations: When collecting it is helpful to have the bottles be intact (not squished or broken) and with the bottle caps present. When building your walls it will be helpful to have bottles of similar sizes. We found that it helps to make at least two rows, one on top of the other, out of the same size bottles. This helps reduce open space between bottles and in-turn reduces cement use. We found that other bottle builders recommend that the bottles be cleaned and dried before placing them in your walls, however, due to a lack of time and abundance of rain, many of our bottles were neither clean nor dry.

To fill or not to fill: Something we asked ourselves and other bottle builders was "should we fill the bottles with plastic garbage, or not?" There are many bottle builders who do fill the bottles with plastic trash before inserting them into the walls. We quickly realized that filling the bottles with trash takes a huge amount of time, as does collecting the trash itself. Through talking with others who have used this construction technique before we found that the most common reason to fill the bottles with trash is to remove the trash from the community, not to ad structural integrity. As our walls were not intended to be load bearing and with the small amount of time we had, we decided it would be better not to fill the bottles. In the future more research could be done into how filling the bottles with trash relates to insulation value.

-

Fig 1: Collect bottles.

-

Fig 2: Build a wood frame.

-

Fig 3: Column prepared for chicken wire attachment.

-

Fig 4: Tie the chicken wire to the columns.

-

Fig 5: Reinforcement for chicken wire on the floor level.

-

Fig 6: Place the bottles in the wall.

-

Fig 7: Tie the both sides of chicken wires with string or metal wire.

-

Fig 8: Slowly rolling chicken wire up the wall as bottles are placed inside.

-

Fig 9: Up close view of bottle orientation.

-

Fig 10: View of outside face of the wall after inside has been plastered.

-

Fig 11: Plastering.

-

Fig 12: Finishing plaster for inside of the walls

Bottle Wall Materials & Budget[edit | edit source]

| Materials | Unit Price (RD$) | Quantity | Total (RD$) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wire ties | Donated | 300+ | $0.00 |

| 1cm Chicken Wire, 3'wide | $66/yard | 58 yards | $3828.00 |

| Staples | $100 | 1 | $100.00 |

| 1x3, Pine | $15/boardfoot | 48 boardfeet | $720.00 |

| Bottles | $0 | 1700 | $0.00 |

| Medium-grain sand | $600/m^3 | 1.25 | $750.00 |

| Portland Cement | $267/ft^3 | 7 ft^3 | $1869.00 |

| 2" Wood Nails | $28/lb | 2 lb | $56.00 |

| 1.5" Concrete Nails | $30/lb | 2 lb | $60.00 |

| Total Cost | $7383.00 | ||

Conclusions[edit | edit source]

A lot of learning took place through the development of this project. The final design of this room met our criteria well and provides a number of benefits, but also has room for improvement

Benefits[edit | edit source]

Comfort: The room contains design aspects that make it quite comfortable. Firstly, it is well shaded by the school and an adjacent apartment building and receives less sun than the rest of the school. It also is well ventilated; there is space below the roof on all sides. While the R-value of bottle walls is yet unknown, the temperature inside the room felt much cooler than outside the room. The bottle walls have much less mass than other walls at the school, which are made of concrete block. The large mass of these walls holds onto heat long after dark. These rooms were consistently hotter, and the air more stagnant than inside the new storage room.

Safety: The building is structurally sound. The walls weigh much less than concrete block walls, and poses less of a threat to occupants if it were to collapse during an earthquake. The slope of the roof is only 6.6 degrees and should not experience a lot of stress from uplifting winds.

Reproducability: The columns and roof are well-known building techniques in the Dominican Republic, and the bottle walls were easily integrated into this framework. With proper documentation, this project has the potential to be easily reproduced at an even lower cost.

Aesthetics: The walls look similar to other plastered walls and can be painted to improve the look. The first wall constructed was not completely straight, and it lends a wavy look to the plaster finish. While aesthetics are very much opinion-based, the general consensus was that it gave the wall character.