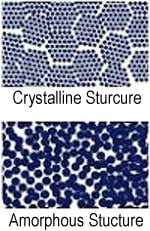

Amorphous metal|Amorphous Metal AlloysW get their name from their amorphous atomic structure. The material has no crystal structure as a result. The amorphous atomic structure is characteristic of glass|glassesW, so the material may be referred to as metal glass. The amorphous structure refers to the disordered arrangment of atom|atomsW in the metal. [1] They generally exhibit greater hardness|hardnessW, Yield (engineering)|yieldW and Fracture|fracture stressesW as well as a comparable modulus of Elastic modulus|elasticityW and Shear modulus|rigidityWthan crystalline metals. The strength comes from the lack of Slip (materials science)|slip planesW on Grain boundary|grain boundariesW that are as a result of a Crystal structure|crystal structureW.[2]

History[edit | edit source]

The amorphous metal structure was discovered in the 1950's when lead foil was Quench|quenchedW at roughly 1012 K/s (degrees Kelvin per second). This resulted in avoiding crystallization during solidification, preserving the amorphous arrangement of the atoms that existed in the metal's liquid state. The cooling of a part requires the dissipation of heat to its surroundings, so the geometry of the part would largely affect its ability to be quenched at a quick rate. The formation of the amorphous structure was limited to foils approximately 50 µm thick.[3]

However, the unique properties of the metal achieved by this process would warrant the creation of a new class of materials: metal glasses, due mainly to their amorphous atomic structure as is characteristic of glasses. The formation of bulk metallic glasses (BMGs) of several centimeters thick soon occurred with advances in processes and materials. In 1969, Chen and Turnbull formed amorphous spheres of Pd77.5Cu6Si16.5 at critical cooling rates of 100 - 1000 °K/s with diameters of 0.5mm.[4]

Forming[edit | edit source]

The major principle contributing to the formation of metallic glass is the quick cooling rate. Longer cooling rates from the Melting point|melting pointW will result in larger grains because the atoms have more time to order themselves into crystals. The rate of cooling can increase to the point that the grains would not only become very small, but soon cease to exist all together. The atom's amorphous arrangement that existed in the metal's liquid state is preserved.[4]

Since the key to the formation of the amorphous structure seems to be the prevention of the formation of crystals, this objective can be addressed directly through disrupting the forces that form the Metallic bond|bondsW themselves. Metals of vastly different size will have difficulty bonding, so an alloy containing them would take longer to crystallize. This arrangement of a vast variety of atomic radii in the same alloy is referred to as the "confusion principle". [4]For the glass to form, the atomic radii of the different metals must differ by at least 12%. [5] Alloys containing an array of elements such as ZirconiumW, AluminumW, NickelW and CopperW can reach critical cooling rates of as low as 1 K/s. The critical cooling rate refers to the lowest rate of cooling at which an amorphous structure can be attained.[6]

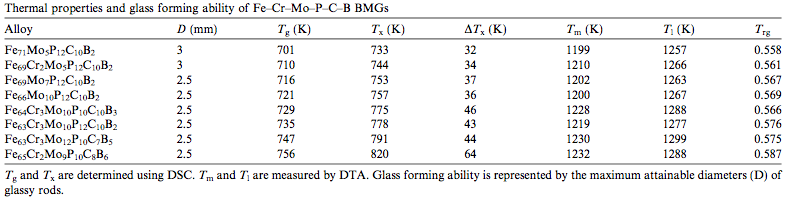

An additional strategy to encourage the formation of glass is choosing the composition of the alloy based on the melting temperature (Tm) and Glass transition|glass formation temperatureW (Tg). The lower Tm and higher Tg is for the alloy, the smaller the difference between the two temperatures, and therefore, the less time required to form a glass at a potentially lower cooling rate. Related temperatures for the formation of BMGs are outlined in Table 1. [2]

|

| Table 1: The glass forming ability of selected BMGs regarding temperature and rod diameter.[2] |

Melt spinning, one of the first process for producing a metal glass, achieved cooling rates on the order of >1000 °K/s. This was necessary for alloys that required such rates for glass formation to occur. The process consisted of pouring a stream of the molten metal over a rapidly rotating drum. The drum was cooled internally with liquid nitrogen. The quick rotation of the drum enabled a thin application of the metal on the drum and for a short amount of time. It was possible to cool a thin quantity of metal that quickly with a conductive method of cooling.

More modern alloys do not require such high cooling rates. This property makes casting a possibility because sufficient cooling can be provided by the walls of moulds. Liquid nitrogen can be used as a powerful agent for cooling the mould wall. Heat can only be dissipated by the outer surface of the metal, so the cooling is still highly dependent on the geometry of the metal part.

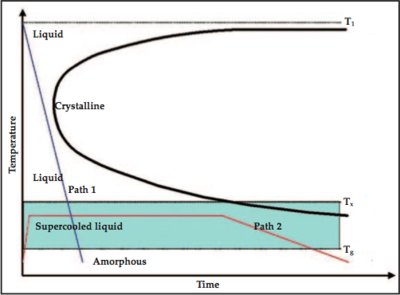

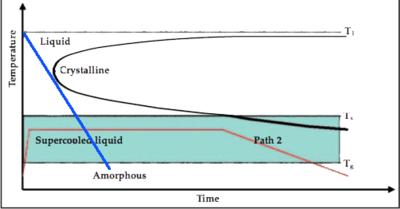

As shown in Figure 3, the formation of the amorphous state is the ability for the cooling curve (the blue line for example) to "miss" the crystalline nose. Lowering the melting temperature (T1 as illustrated in the plot) and raising or maitaining the glass formation temperature, as shown in Figure 4, would yield a cooling curve with a lesser slope, and therefore lower cooling rate, that misses the cryslalline nose.[3]

|

|

| Figure 3: Cooling diagram. [3] | Figure 4: Cooling diagram showing lower melting temperature. [3] |

Mechanical Properties[edit | edit source]

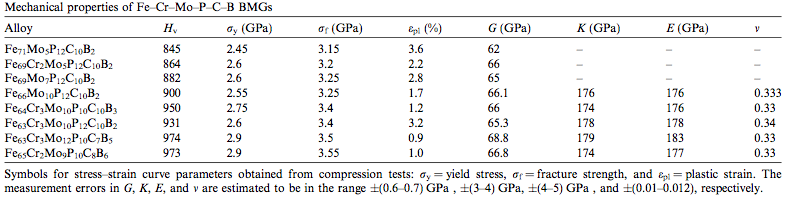

The amorphous structure of these glasses results in a lack of Slip (materials science)|slip planesW that would normally exist in a material with Crystallite|grainsW and Grain boundary|grain boundariesW. As a result, metal glasses exhibit much greater resistance to Deformation (mechanics)|deformationW than crystalline metals. This property generally leads to a much greater Vickers hardness test|Vickers hardnessW (Hv), Yield (engineering)|yield stressW (σY) and Fracture|fracture stressW (σf) as demonstrated by Table 2. Other properties outlined are the modulus of Elastic modulus|elasticityW (E), modulus of Shear modulus|rigidityW (G), Bulk modulus|bulk modulusW (K) and Poisson's ratio|poisson's ratioW (v) which are comparable to that of other existing engineering materials. [2]

|

| Table 2: Stress-strain curve parameters obtained from compression tests of BMGs. [2] |

Grain boundary|Grain boundariesW are also a weak point for Corrosion|corrosionW as they provide more surface area for the required chemical reactions to occur. The lack of grain boundaries in BMGs reduce their tendency to corrode.[7]

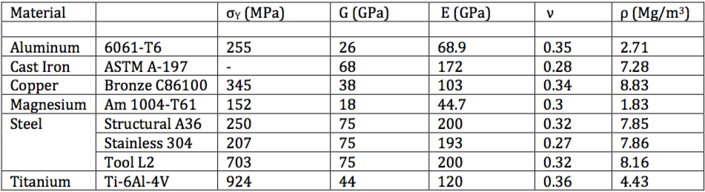

For comparison, properties of some common engineering materials are given in Table 3.

|

| Table 3: Properties of common engineering materials.[8] |

It is evident that the Iron based BMGs examined in Table 2 have approximately 3 times the yield stress of titanium Ti-6Al-4V and over 10 times the yield stress of structural steel A36 with comparable modulus of elasticity and rigidity.[8] Their high yield stress and therefore high resistance to deformation gives metal glasses very high elasticity and ability to store mechanical energy.[4]

Because of the stiffness of BMGs, they are considered to have poor ductility and therefore poor tensile strength. When a significant tensile load is applied, they experience a phenomenon refered to as shear banding which occurs as a result of localized shear.[7]

Forming methods[edit | edit source]

Die Casting[edit | edit source]

When Die casting|die castingW materials such as iron, their net volume can reduce significantly over the cooling process, yielding an inaccurate part and therefore requiring Surface finishing|surface finishingW afterwards. Die casting metal glass parts is very practical because there is almost no shrinkage. This happens for two main reasons. Firstly, the formation of glass is such that the arrangement of atoms in glass is the same as the liquid, so there is essentially no Phase transition|phase changeW. Since the atoms do not rearrange, the volume of the die does not change and therefore no shrinkage. Secondly, the alloys possessing low Tm will require less cooling than most Carbon steel|carbon steelsW for example. A smaller temperature change also leads to less contraction during cooling. These properties of metal glasses will lead to Near net shape|near net shapeW die cast parts with little need for additional Surface finishing|surface finishingW after casting. [3]

Thermoplastic Forming[edit | edit source]

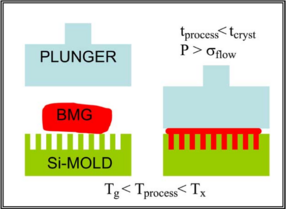

|

| Figure 2: A rough schematic of the elements involved in the thermoplastic forming of BMGs. [9] |

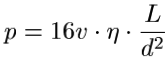

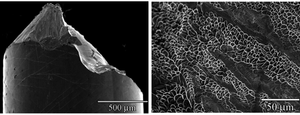

BMGs can be formed into relatively complicated shapes by thermoplastic forming. When the glass is at a temperature slightly above Tg, it is plastic enough to be deformed without fracturing. An Ingot|ingotW of metallic glass is pressed into a die as shown in Figure 2. Since the forming process occurs at above Tg, the glass has not set and can still crystallize if left at this temperature for a too long. Certain alloys of BMG's are resistant enough to crystallizing that enough time exist to carry out the thermoplastic forming process while maintaining desired the properties of the part. We know that BMGs are limited to smaller geometriess but they also have low shrinkage during cooling. These traits make thermoplastic forming applicable for the formation of small parts. The average pressure required to carry out the formation of a part is expressed by the Hagen–Poiseuille equation.[9]

L is the length of a channel, d is the diameter, η is the viscosity of the BMG, ν is the velocity at which it is moving down the channel and p is the pressure required for the process. The model suggests that the feasible maximum forming pressure and therefore minimum feature diameter are approximately 300 MPa and 10nm.[9]

Process Energy Reduction[edit | edit source]

The most obvious method of reducing the energy required to produce amorphous metals is to create metals with lower melting points. If the melting point is lower, less energy has to go into heating the metal up to the appropriate temperature. Conversely, the energy efficiency of the process for rapidly cooling the metal would be improved by the lower melting temperature because less energy would be required to cool the metal over a lesser temperature difference. A slower critical cooling rate is more likely with a lower melting temperature so more of the effect of cooling can be lent to the ambient temperature. A substantial amount of energy is required to force cooling to achieve faster cooling rates than that which would be achieved by conventional quenching. Decreasing the critical cooling rate primarily would reduce energy consumption for the mentioned reasons.

The implementation of Squeeze casting to the process of producing BMGs can increase its efficiency. Squeeze casting is essentially performing a casting process at pressures on the order of 100Mpa. During solidification, high pressure causes the liquid metal to maintain contact with the mould wall throughout the process. The mould wall provides the cooling to the material. This improves the efficiency of heat removal, increasing the rate of cooling that can be achieved. The melting temperature and the glass forming temperature of metals increase at higher pressures. So melting the metal at a lower pressure and casting it at an increased pressure would essentially decrease the temperature difference that the cooling process would have to achieve.[10]

Methods for increasing the efficiency of the thermoplastic forming process can be hypothesized upon inspection of the Hagen-Poiseuille equation. An increase in efficiency would be achieved it the velocity of the process were increased and the pressured required were decreased or maintained. A higher velocity would decrease the amount of time that the thermoplastic forming process requires, lending more time to the cooling process once the final shape of the material has been established. This could easily be obtained by changing the geometry of the part that is to be formed. Decreasing the length and increasing its diameter while maintaining the pressure would increase the velocity of the forming process. Decreasing the amount and intricacy of features on the part will yield the same effect as increasing the diameter. Decreasing the viscosity of the metal during the process would increase its efficiency. This could be achieved by either changing its composition to less viscous metal or by performing the process at as close to the glass forming temperature as possible. [9]

Limitations[edit | edit source]

Despite several positive traits of metallic glasses, several limitations of the material still exist. Due to its high strength, it generally exhibits a low elastic strain limit. The material will not deform under load, but rather fail catastrophically when the fracture stress is reached. This can be dangerous in structural application because few visual cues are given if the material is about to fail.

Though the formation of metallic glasses has evolved from thin impractical foils to modern BMGs of several centimeters in diameter, they are still limited to parts of small thickness and awkward geometry.

Various process for producing metallic glasses are still in their infancy, so adoption and therefore production of the material is not yet wide spread. Production costs are far higher than conventional crystalline alloys so they are limited to applications. The process can become more economically feasable in the future as facilities are expanded to accommodate the up scaling of the process. Just like today's mass produced materials such as steel, producing BMGs in such high quantities would likely offset much of the overhead costs per unit of product associated with small scale production.

Metal glasses are limited to low temperature applications because of their characteristically low glass formation temperatures. If they were to be placed in an environment that exceeds their glass formation temperature, they would loose their amorphous property and likely reform into a crystalline metal.[7]

Applications[edit | edit source]

Metal glasses have found applications in high end markets where any performance gain from utilizing them in the product is justified, regardless of the cost. They have begun to appear in higher end electronics as cases due to their rigidity, hardness and therefore scratch resistance. The high hardness is ideal for use in tooling. The lack of grain structure allows a blade to be sharpened to an exceptional edge because there is no length scale above the atomic to limit it. This property is useful in knives, especially in scalpels.

High elastic energy storage per unit volume and mass, and the low damping, give metallic glasses potential as springs. Sporting equipment such as golf clubs and baseball bats utilize the high hardness and elastic energy property for good energy transfer to projectiles.They were successful used in golf club heads and in tennis racket frames where the property is exploited. Other possible applications of springs in devices are high-speed relays.

Information storage and reproduction would utilize the lack of grain structure and high hardness. Features of near-atomic scale could be moulded or etched into a metallic glass surface to make masters for reproducing ultra-high density digital data.[7]

Small parts can be die-cast to achieve a near net-shape fabrication where additional machining to achieve the shape would be expensive and impractical.[4]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Technology Liquidmetal Technologies." Liquidmetal Technologies. N.p., n.d. Sat. 07 Nov. 2009.;http://web.archive.org/web/20110518094601/http://www.liquidmetal.com:80/technology/default.asp;

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Gu, X., Poon, S. J., Shiflet, G. J., Widom, M. (2008). Ductility improvement of amorphous steels: Roles of shear modulus and electronic structure. Acta Materialia, 56, 88-94.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Schroers, J., Paton, N. (2006). Amorphous Metal Alloys Form Like Plastics. Advance Materials Processes, January 2006, 61-63.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Telford, M. (2004). The Case for Bulk Metallic Glass. Materials Today, March 2004, 36-43.

- ↑ Lee, H., Cagin, T., Johnson, W. L., Goddard III, W. A. (2003). Criteria for formation of metallic glasses: The role of atomic size ratio. Jornal Of Chemical Pysics, 119(18), 9858-9870.

- ↑ Telford, M. (2004). The Case for Bulk Metallic Glass. Materials Today, March 2004, 36-43.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Ashby, M., Greer, A. (2006). Metallic glasses as structural materials. Scripta Materialia, 54, 321-326.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 R.C. Hibbeler, Mechanics of Materials, third edition, Prentice Hall, 1997.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Schroers, J., Pham, Q., Desai, A. (2007). Thermoplastic Forming of Bulk Metallic Glass— A Technology for MEMS and Microstructure Fabrication. Journal of Microelectromechanical Systems, 16(2), 240-247.

- ↑ Kang, H. G., Park, E. S., Kim, W. T., Kim, D. H., Cho, H. K. (2000). Fabrication of Bulk Mg-Cu-Ag-Y Glassy Alloy by Squeeze Casting. Materials Transactions, 41(7), 846-849. Retrieved November 9, 2009, from the The Japan Institute of Metals database.