Geothermal power

For the energy source of geothermal power, see Geothermal energy.

Geothermal power is generated from the high temperatures that can be found in various parts of the Earth's crust such as volcanoes, hot springs, and geysers.[1] The high temperatures range from 107º C (225º F) to 315º C (600º F)[2] and occur in these areas due primarily to the decay of radio-active isotopes that occur within the rocks of the earth's crust.[3] The water that surrounds and fills the gaps between the rocks in the crust is raised in temperature by these natural processes. This hot water is then pumped to the surface and its steam is captured and used to create electrical power through a turbine system.

There are three common types of geothermal power: dry steam, flash steam, and binary cycle. Dry steam is rare and uses the steam directly from the earth, flash steam pumps the hot water that naturally occurs in the earth to the surface and utilizes its steam, and binary cycle uses a secondary fluid and its vapor to power a generator.[4]

In addition, there are new, smaller types of geothermal that are not as site-dependent as traditional, large-scale systems.

Traditional systems[edit | edit source]

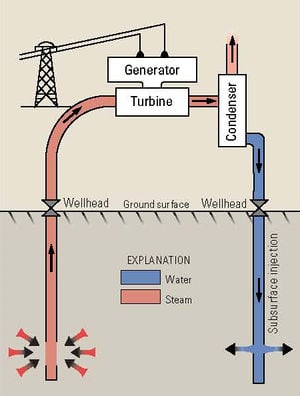

Dry Steam[edit | edit source]

Dry stream geothermal plants use natural steam directly from the Earth. This natural steam is created by the natural geothermal heating of an underground pocket of water deep below the earth's surface. Once the steam pocket is tapped, the steam is channeled directly into a turbine which converts the thermal energy into electrical power. These systems are very rare; not many places on Earth have large enough pockets of natural steam to provide sufficient incentive to create a dry steam plant.[5]

The only dry stream power producer that is located in the United States is a series of plants called "The Geysers", which make up the largest dry steam systems in the world. Located in the Mayacamas Mountains, just north of San Francisco, The Geysers generate a net capacity of about 725 megawatts of electrical power - enough to power 725,000 homes, or a city the size of San Francisco.[6]

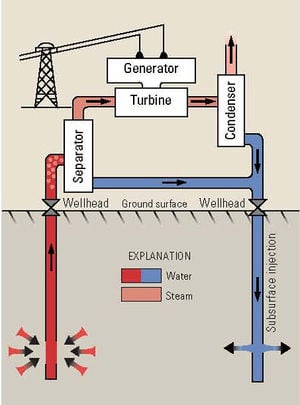

Flash Steam[edit | edit source]

Flash stream power is the most common type of geothermal power due to its efficiency; the hot water from the earth can be reused to produce more steam. Flash steam geothermal occurs in areas naturally greater than 360º F in the earth's crust. The hot water from these areas is pumped up to the surface of the earth, where its pressure is lessened and it is separated into steam and cool water. The steam is then collected and sent to a turbine to generate electrical power, while the cooled water is pumped back down to the geothermal area in the crust to continue in the cycle..[7]

Built in 1969, Iceland's very first geothermal plant, the Bjarnarflag Geothermal Plant, is a flash steam plant located in North Iceland. Bjarnarflag takes the steam produced from the hot water in the ground to generate 3 megawatts of electrical power. The water that is separated from the steam in this plant is used to heat the fresh water used for district heating in Bjarnarflag.[8]

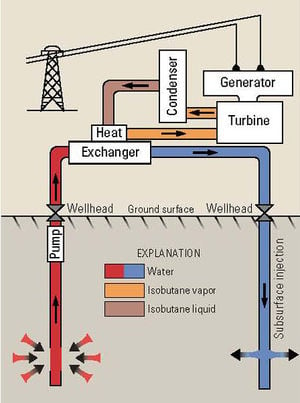

Binary Cycle[edit | edit source]

Power from the geothermal binary cycle is generated through the use of another liquid in addition to water. This type of geothermal power is used in areas in the crust that have naturally lower temperatures that that used in flash steam (225º F-350º F). Water is pumped from the source to the surface where a secondary liquid with a much lower boiling temperature than water's is introduced. The small amount of heat that the water carries is used to vaporize the secondary liquid through the use of a heat exchanger; that vapor is sent to the turbine to generate electrical power. These two liquids never come into contact with each other; the water's heat is only used to vaporize the secondary liquid. After the vapor is collected, the water returns to the source to complete the cycle again.[9]

A binary cycle geothermal plant is located in Wairakei, New Zealand. The Wairakei Geothermal Power Station was commissioned in 1958; it was the first of its kind in the world at the time. Wairakei Geothermal Power Station is capable of generating 181 megawatts of power using the binary cycle, enough to power about 150,000 homes.[10]

Experimental systems[edit | edit source]

Because Earth's surface is fairly thin compared to the full width of the globe, drilling down a comparatively shallow depth allows one to get heat to power systems virtually anywhere in the world.[11]

Utilized areas[edit | edit source]

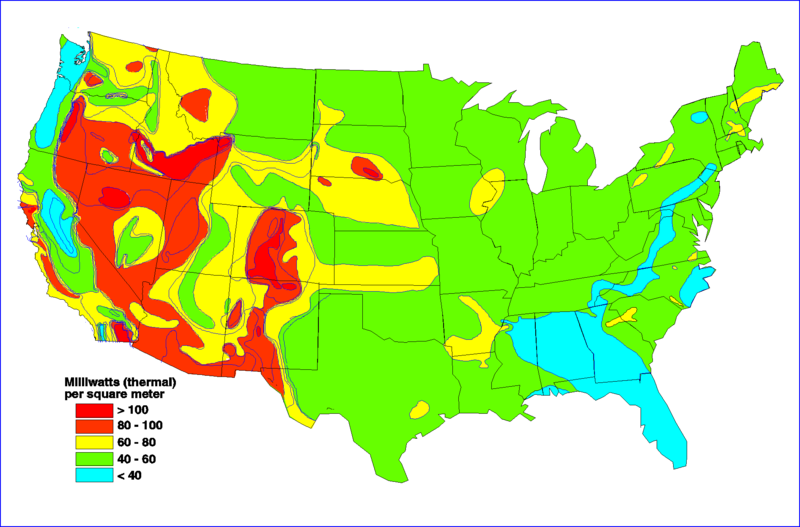

There are multiple areas that are available for geothermal use in the world. Iceland currently generates 25% of its electrical power from geothermal systems.[12] Geothermal energy is used to make up about 10% of New Zealand's electrical power supply.[13] And in the United States there are plants located in Alaska, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Nevada, and Utah. In 2005, geothermal energy generated 25% of domestic, non-hydroelectric, renewable, electrical power in the U.S.[14] Many places in Central America are also utilizing their high geothermal activity. The region is a leader in research and development and execution of geothermal power projects. Countries that have projects implemented are Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Guatemala, and El Salvador.[15] While many of the hot spots are being used resourcefully in the world, many seismically active areas are not.

Under-utilized areas[edit | edit source]

In order for geothermal power to be considered a possibility, the plant must be located in a part of the globe that is seismically active. This allows for a continuous source of heat where the water is being pumped. The active areas include: the Western United States, Iceland, New Zealand, the Philippines, and South America.[16] The United States has geothermal activity in Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming.[17] However, most of these resources are not being utilized.

Further reading[edit | edit source]

- Wikipedia page: Geothermal electricity

- United States Geological Survey Assessment: Assessment of Moderate- and High-Temperature Geothermal Resources of the United States

- Development of Central American Geothermal Projects:Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Guatemala, El Salvador

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ http://web.archive.org/web/20180326003808/http://iceland.ednet.ns.ca:80/schedule.htm

- ↑ http://web.archive.org/web/20120824114035/http://www.energysavers.gov:80/your_home/electricity/index.cfm/mytopic=10470

- ↑ Duffield, Wendell A. and Sass, John H. Geothermal Energy—Clean Power From the Earth's Heat. U.S. Geological Survey: Circular 1249 [1]

- ↑ http://web.archive.org/web/20120824114035/http://www.energysavers.gov:80/your_home/electricity/index.cfm/mytopic=10470

- ↑ http://www.daviddarling.info/encyclopedia/D/AE_dry_steam_geothermal_plant.html

- ↑ http://www.geysers.com/

- ↑ http://www.technologystudent.com/energy1/geo4.htm

- ↑ http://web.archive.org/web/20141110140053/http://www.mannvit.com:80/GeothermalEnergy/GeothermalPowerPlants/GeothermalProjectBjarnarflag/

- ↑ http://www1.eere.energy.gov/geothermal/powerplants.html#binarycycle

- ↑ http://web.archive.org/web/20100604035618/http://www.contactenergy.co.nz/web/pdf/environmental/Geothermal_brochure.pdf

- ↑ You Can Have Geothermal Power Everywhere If You Drill Deep Enough by Lloyd Alter (2022-02-23), published by Treehugger.

- ↑ http://www.nea.is/

- ↑ http://www.nzgeothermal.org.nz/elec_geo.html

- ↑ http://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2008/3082/pdf/fs2008-3082.pdf

- ↑ http://web.archive.org/web/20100610100627/http://www.geo.mtu.edu/~refish/Resource%20pages/GEOTHERMAL%20RESOURCES.html

- ↑ http://www.altenergy.org/renewables/geothermal.html

- ↑ http://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2008/3082/pdf/fs2008-3082.pdf