Core Knowledge and Competencies - Osteomyelitis

Objective:

In this Module, you will learn core knowledge and competencies needed to evaluate, diagnose, and manage osteomyelitis.

Basic Terminology and Anatomy[edit | edit source]

By the end of this Module, you will be able to:

- Understand basic knowledge related to osteomyelitis, including terminology, anatomy, and pathophysiology

- Gain confidence in your ability to correctly evaluate and diagnose osteomyelitis.

- Understand the basics of osteomyelitis anatomy, i.e., sequestrum, involucrum, abscess, cloaca, and sinus.

- Understand the basics of osteomyelitis management including debridement, stabilization, and the role of antibiotics and nutrition.

- Understand how to provide post-operative care for osteomyelitis, including addressing any complications that may arise.

What is Osteomyelitis?[edit | edit source]

Osteomyelitis is infection of bone resulting from trauma or blood infection (bacteremia). Management of bone infections can be challenging and expensive. Osteomyelitis in the pediatric population is most often the result of hematogenous seeding of bacteria to the metaphyseal region of bone. Diagnosis is generally made with MRI studies to evaluate for bone marrow edema or subperiosteal abscess. Treatment is nonoperative with antibiotics in the absence of an abscess. Surgical debridement is indicated in the presence of an abscess.

You will use this rubric to assess your own knowledge and skills and to measure your progress over time as you learn more about evaluating, diagnosing, and managing osteomyelitis.

Assessment Rubric for Learning Target 1: I have the basic knowledge required to confidently diagnose and manage osteomyelitis.[edit | edit source]

| SKILLS: | EMERGING (I am just getting started on this skill) | APPROACHING (I am still developing this skill) | MEETS (I am competent and confident in this skill) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Understand basic knowledge (terminology, anatomy, and pathophysiology) related to osteomyelitis | I am starting to learn basic knowledge about osteomyelitis. | I understand most basic knowledge about osteomyelitis. | I am confident in my basic knowledge about osteomyelitis. |

| 2. Evaluate and diagnose osteomyelitis | I am starting to learn to evaluate and diagnose acute and chronic osteomyelitis. | I can reliably identify on x-ray the anatomical findings of chronic osteomyelitis. | I am confident in my ability to correctly evaluate and diagnose osteomyelitis. |

| 3. Manage osteomyelitis (including understanding basic anatomy of osteomyelitis, i.e., sequestrum, involucrum, abscess, cloaca, sinus) | I am starting to learn basic concepts of managing osteomyelitis. | I can reliably manage and prepare a treatment plan, based on findings, to care for a patient's osteomyelitis. | I can correctly and consistently execute a treatment plan, medical management, and surgical treatment of osteomyelitis. |

| 4. Provide post-operative care | I am able to provide basic instructions for nursing staff and patient/family for post-operative care. | I am able to monitor for and identify post-operative complications. | I am able to address complications that may arise from injury/treatment. |

Osteomyelitis Curriculum[edit | edit source]

1. Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

How do bacteria get into the bone...what are the portals of entry?

- Haematogenous: Septic embolus from innocuous distant focus

- Direct penetration: Puncture wound, compound fracture.

- Spread from contiguous organ – gut, urinary tract, respiratory tract: More common in neonates and immunocompromised people. Often unusual organisms or TB. Spine and pelvis more frequently involved.

In this course we will be concentrating on the surgical treatment of haematogenous osteomyelitis in children since it is so common in low resource environments.

Why is bone vulnerable?

- Certain bacteria have a predilection for bone, especially staphylococcus.

- The spongy metaphyseal bone acts as a filter.

- The metaphyseal sinusoidal blood supply is sluggish with a lack of protective endothelium.

- Metaphyseal sinusoids have immature and poorly developed protective reticuloendothelial cells.

- Direct blunt trauma is known to predilect bone infection, so subcutaneous and exposed bone is vulnerable, especially above or below the knee.

Why is osteomyelitis so common in lower-income countries?

- More exposure / portals of entry: running around barefoot over rough and sharp surfaces with numerous subclinical puncture wounds. More potential for direct trauma & bruising.

- Unhygienic surroundings: including limited water supply for cleansing, exposure to dung floors, foot wounds from jiggers, skin sores and wounds, etc.

- Host immunocompromise, mainly malnutrition and anemia related. Most common in 9mo. to 3 year olds.

- Unavailable or delayed initial treatment resulting in more pathology and chronicity

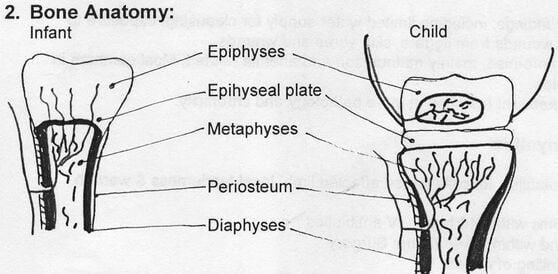

2. Bone Anatomy[edit | edit source]

Vascular anatomy:

Nutrient arteries perforate the diaphyseal cortex, pass through nutrient foramina into the haversian system, and into the medullary canal. They then ramify along the endosteal surface to provide the endosteal supply system. The external cortex is supplied by periosteal feeders forming the periosteal supply system. The epiphyses is supplied by feeders from the joint capsule, forming the epiphyseal supply system.

In children with ossifying epiphyses, vessels do not cross the epiphyseal plate, which therefore forms a barrier to bacterial invasion. In infants with a cartilaginous epiphyses, however, metaphyseal vessels do cross into the epiphyses.

The uniqueness of the juxta-epiphyseal metaphyseal blood supply:

The endosteal system end-arteries terminate in large sinusoids which have no endothelium. Flow is sluggish, and interrupted by the developing enchondral bone columns. There are few cells of the reticuloendothelial system to counterattack infection.

3. Acute Hematogenous Osteomyelitis[edit | edit source]

- Age: Infancy and childhood, rarely at other ages

- Gender: Males 4:1

- Location: Metaphyses of rapidly growing long bones

- Predisposing factors: Trauma - history of direct blow often elicited Antecedent focus of infection (boil, tonsilitis) Poor nutrition, unhygenic surroundings

- Recognition: Fever, malaise, irritability, inability to use affected limb, local tenderness & warmth

Primary treatment:

- Onset of symptoms within 48 hours: IV antibiotics

- Failure to respond within 36-48 hours: Surgery

- Surgery: Incision & Drainage, drilling of cortex

Differentiation from Pyomyositis: explore the abscess to see if it goes down to bone

Antibiotics: IV until systemic signs resolve, then oral x 6-8 weeks altogether. Symptoms vulnerable to recur if treatment stopped early. Some say keep up oral antibiotics until ESR returns to normal.

Organisms:

- Neonate: Group B Strep, Coliforms, Staph.

Antibiotics: Cloxacillin / Gentamycin / Chloramphenecol

- Infants & Children: Staph Aureus.

Antibiotics: Cloxacillin or Cephalosporin

Drilling the bone for acute osteomyelitis

Early osteomyelitis may not show up on an x-ray until 10 to 14 days after onset. When palpating the abscess, if it goes down to the bone, it is must be considered osteomyelitis. In this case drill the bone to decompress the medullary cavity. This reduces the risk of the pressurized pus stripping the endosteal blood supply creating a large sequestrum. Drill 2 or 3 small holes. If only medullary fat expresses, and not pus, nothing further need be done. If pus comes out under pressure, drill several larger holes.

4. Pyomyositis[edit | edit source]

Pyomyositis is seen in tropical environments where there is poverty and malnutrition. It affects mainly large muscle groups in children and young adults. There is severe local pain in the muscle group, inability to actively move the muscle, and pain when the muscle is stretched. Abscesses may be deep and difficult to palpate.

The differential diagnosis is osteomyelitis. An x-ray should be done to exclude bone changes.

The organism is usually Staphylococcus. Treat with appropriate antibiotics. If the patient has systemic symptoms, start with intravenous antibiotics and shift to oral antibiotics once the acute systemic signs are settling.

Drainage of a pyomyositis abscess

"Where there is pus, let it out"

Do not try to treat an abscess with antibiotics alone! Antibiotics do not penetrate abscess cavities. Surgical drainage of abscesses is always necessary! If there is any question, incise and drain.

The initial skin incision should be adequate to accommodate a finger so that the finger can be inserted into the abscess cavity in order to assure that the cavity has been completely drained. Palpate the abscess cavity carefully. If bone is not felt and the abscess appears to be entirely within muscle, it is pyomyositis. The cavity is then irrigated and, except for tiny superficial ones, a drain is left in place or the wound is packed with gauze to assure continued drainage. The prognosis is good once the abscess is drained.

5. Chronic Osteomyelitis[edit | edit source]

- The initial infection is metaphyseal, creating a lytic abscess cavity.

- Pus rapidly develops under pressure and forces it's way along paths of least resistance: Down into the medullary canal.

- Out through a cortical breach or nutrient foramina.

- The metaphyseal cortex is egg shell thin and easily breached, and has a weaker periosteum, so a subcutaneous abscess is formed.

- Pus spreading down the medullary canal strips endosteal blood supply system, necrosing endosteal and trabecular bone.

- Nutrient foramina allow direct extension from medullary cavity to sub-periosteal space.

- Pus expanding beneath the periosteum strips it from the periosteal cortical surface, causing necrosis.

- Thus the whole diaphyseal cortex dies, forming the sequestrum.

The periosteum is resistant to damage from infection and survives in most cases. It's cells immediately begin the process of appositional new bone growth, laying down bone in a fusiform concentric manner, forming the involucrum.

Bone sinuses from the sequestrum out through the involucrum are called cloacae.

This pathologic process can then result in variable radiographic appearances.

6. Classification of Chronic Osteomyelitis[edit | edit source]

- Typical (sequestrum / involucrum). A sequestrum can be seen as a sclerotic segment of bone separate from the surrounding involucrum. There is a lucent line around the sequestrum representing pus and granulation tissue. Involucrum bone has formed around the sequestrum to various extent. The involucrum is immature woven bone, not typical haversian or trabecular bone. Treatment: Sequestrectomy. Remove all dead bone through a cortical window and curette the bone cavity.

- Atrophic. Failure of the involucrum to form. The sequestrum may span the bone ends but there is little or no surrounding involucrum. A segmental bone deficit will occur when the sequestrum is removed. Treatment: Complex! Wait 6 months or more for involucrum to form. If no involucrum forms, reconstruction is necessary after sequestrectomy.

- Sclerotic.A fusiform dense sclerotic healing reaction, narrowing or obliterating the medullary cavity. Represents a healthy and overactive periosteal response with the infected bone acting as a stimulant to appositional new bone growth. Sequestrae may be locked within but not seen on X-Ray due to dense bone reaction. Look hard for subtle signs of sequestrum. Overpenetrating the Xray can help to identify. Treatment: Saucerization.

- Walled off abscess(es). Several localized well identified radiolucencies within ample involucrum. Sometimes a nidus is seen, representing sequestrum. More usually seen in the metaphyseal region, but extends into the new woven bone of the involucrum. Usually seen where the healing reaction is vascular, brisk and effective, and demonstrating the ability of the body to absorb or eject significant portions of necrotic bone leaving isolated trapped islands. Treatment: Saucerization

- Isolated metaphyseal cyst. Single or multiple walled off abscesses which may or may not have a sclerotic margin. Erosion of cortex can occur if juxta-cortical. There are no typical cortical sequestrae, although there may be micro-sequestrae from trabecular necrosis. Treatment: Drill a cortical window, curette the cavity.

7. Surgical procedures for Chronic Osteomyelitis[edit | edit source]

Surgical Principles

- Plan surgery taking into consideration:

- Standard surgical approaches

- X-ray anatomy of involucrum/sequestrum

- Location of major sinus tracts and skin involvement

- Avoid if possible surgical approaches directly over subcutaneous bone surfaces (esp. tibia).

- Look very carefully at the X-Ray and correlate with surgical findings. Make sure to get all involved sequestrae & cavities. Plan the approach to remove the thinnest portion of involucrum and avoid removing vital supportive bone.

- Minimize periosteal stripping to area of saucerization so as minimize disruption of blood supply.

- Get rid of all dead bone & infected material. Be suspicious of retained small fragments of sequestra and thoroughly explore the bone cavities. Be aware of secondary walled off cavities and sequestrae clinging to the endosteal surface.

- Sequestrectomy vs. saucerization. Make a LARGE window in the bone using a drill to map it out, and a gouge to give a curved upper and lower border to limit potential pathologic fracture. Use existing cloacae where present, or centralize over main cloacae. Adequately saucerizing bone is as important as finding the sequestrum. Most failures of surgery are due to inadequate saucerization and bone excision. Be aggressive!

- Explore sinuses. These often lead to secondary sequestra or pieces loose within soft tissue, and give a clue as to location of cloacae. Curette out all infected granulation tissue.

- Culture for bacteria. Although staph aureus is the most common, other organisms occur, particularly in sickle cell disease

- Biopsy for Acid Fast Bacilli. Always be suspicious for TB osteomyelitis. "Always culture when you biopsy, always biopsy when you culture"

- Fill dead space. Sculpt edges of saucerized bone to lower the profile of prominent bone, and use neighbouring muscle to fill the cavity. This is quite easy with humerus or femur, but difficult in the tibia.

- Allow drainage. Use drains, loosely packed. eg. vaseline gauze, penrose drains, cut fingers of surgical gloves..

- Loose wound closure. This is better than leaving the whole wound open, which takes a long time to heal and may result in necrosis of exposed bone.

- Antibiotics not necessary. Removal of dead bone is the curative act in chronic osteomyelitis. The infection is walled off from systemic spread. Antibiotics should be used primarily to combat systemic symptoms. Antibiotics for a few days peri- operatively are not unreasonable.

Bone surgery: Curetting a metaphyseal abscess

An incision is made over the abscess.

If there is a sinus, follow it down to the bone.

The bone is exposed using a periosteal elevator.

A drill is used to drill out a cortical window 2 cm in diameter.

A bone curette is used to enter and curette out the bone abscess.

All necrotic bone and granulation tissue should be removed.

Look carefully for small micro-sequestrae.

Once the abscess is fully evacuated curette all the edges to feel for a uniform bone consistency.

Irrigate the cavity with saline.

Insert a drain. This may be a simple gauze sponge, or latex Penrose drain. Cutting the finger off a surgical glove and inserting it works effectively.

Do not use any subcutaneous sutures, they become a focus of infection.

The incision may be closed loosely ensuring enough drainage space. Use monofilament nylon sutures in the skin if available.

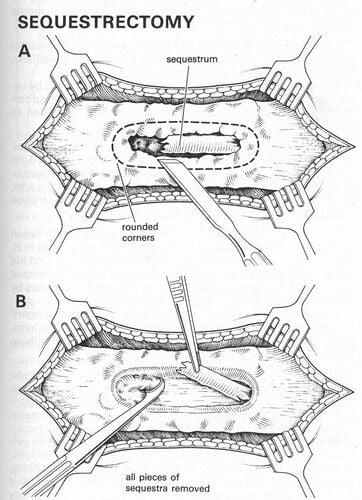

Bone Surgery - Sequestrectomy

A lengthy incision is usually required. Follow the appropriate anatomic planes.

Avoid putting incisions over the subcutaneous border of bones, notably the tibia. Put the incision over the adjacent muscle instead. Follow the sinuses to get to the cloacae. They are often the best clue as to where the sequestrum lies.

Use a periosteal elevator to strip enough periosteum to see the bone adequately.

Avoid circumferential periosteal stripping which compromises vascular supply to the involucrum.

Use a drill to map out a large cortical window at the cloaca, or exposed sequestrum. Make the cortical window oval in shape with rounded corners to avoid stress fracture. Use a bone nibbler (rongeur) to trim back the bone as necessary.

Grasp and remove the sequestrum. It may take considerable bone resection to free it up. Use a bone curette to clean out the cavity. There are often retained bits of sequestrum. Healthy bone has a dull, woody feel to the curette; sequestrum has a sharp metallic feel. Feel the edges of the cavity very carefully. Sequestrum can stick to the lining of the involucrum.

Once the cavity is cleaned out, look for adjacent muscle to transfer into the defect. Insert one or more drains.

Do not use any subcutaneous sutures.

Close the skin loosely, leaving substantial gaps for drainage around the drains.

Bone Surgery - Saucerization (partial diaphysectomy)

Removing the entire sequestrum can be difficult, particularly if it has broken up into several segments, occupies a large length of the medullary canal and if there is a healthy involucrum response capturing and walling off the sequestrum. It is also needed in cases of multiple walled-off abscess formation over a large segment of the diaphysis. In this case a "saucerization" is required. It is an extension of the sequestrectomy procedure illustrated above. In this procedure a large window is made in the involucrum over 5 or more centimeters, exposing the medullary canal to liberate all segments of sequestrum. A drill is used to map out the cortical window and a portion of the diaphysis, consisting usually of about one third the diameter, is removed. Care must be taken to remove the weakest portion of the involucrum, leaving healthy involucrum behind to act as structural bone. This procedure can only be done where there is a healthy involucrum response. Saucerization can be considered a partial diaphysectomy, or making a "canoe" out of the involved bone.

A lengthy surgical exposure is necessary. Make the incision over muscle and not over the subcutaneous border of the bone. Wherever possible allow muscle to fall into the cleaned medullary canal, or transfer muscle in order to fill the dead space. Close the wound loosely over drains.

8. Basic bone instruments[edit | edit source]

Most osteomyelitis surgery can be accomplished with a set of basic bone instruments. Unfortunately, these are not always available at district hospitals. There are many variations of orthopaedic instruments.

Hand drill. Sometimes called a Zimmer drill. There is a smaller version called the Bunnell drill. Used for drilling holes through the cortex to decompress the bone, to remove a cortical bone window, or to do a saucerization.

Osteotome. For cutting bone like a chisel. There are various sizes. An osteotome is beveled on both sides of the blade while a chisel is beveled only on one side

Mallet. For use with the osteotome or a bone gouge.

Bone lever. Goes around the bone under the periosteum to act as a retractor of soft tissues. Once around the bone it levers the muscles away. Two are usually used. There are many varieties and shapes of bone levers.

Periosteal elevator. Used to strip the periosteum off the bone with a scraping motion.

Bone curette. Used to scrape cavities of necrotic bone and fragments of sequestrum.

Bone Rongeur (Bone Nibbler). A punch cutting forceps that bites and removes bone in small fragments. Used to open cortical windows to perform sequestrectomy and saucerization

- https://storage.googleapis.com/global-help-publications/articles/techortho_chronicosteomyelitis.pdf

- https://www.orthobullets.com/pediatrics/4031/osteomyelitis--pediatric

Refer to the rubric in Step 3 (you may want to print out one or more copies). Use the rubric to assess the following and note if you are EMERGING, APPROACHING, or MEETING each of the sub-skills. This will help you know which knowledge and sub-skills require more review. Please take notes on your self-assessment below.

- Row 1: How confident are you in your basic knowledge about osteomyelitis?

- Row 2: How confident are you in your ability to consistently and correctly evaluate and diagnose osteomyelitis?

- Row 3: How confident are you in your ability to correctly and consistently manage a patient's osteomyelitis and prepare a treatment plan?

- Row 4: How confident are you in your ability to provide post-operative care, including identifying and managing any treatment complications?

SELF-ASSESSMENT NOTES:

Once you have determined that you MEET all of the sub-skills, you can move on to the next Module, where you will build your bone drilling simulator.