The Model

There are four ways for a culture to exist.

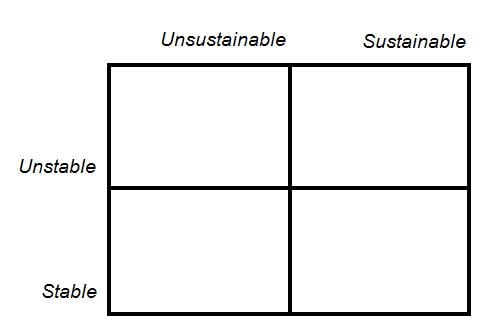

It can be either stable or unstable, and it can be either sustainable or unsustainable. These four descriptors reduce economic, social, historical, ethnic, linguistic, and religious complexity to a simple matrix.

- If a culture is stable, it is under no immediate threat of dissolution. It can continue as-is at least into the mid-term future.

- If a culture is unstable, it is under threat of dissolution. It may appear to be stable into the short-term, but it'll soon turn to chaos.

- If a culture is sustainable, then its practices are tenable in the long-term and could carry the culture forward indefinitely.

- If a culture is unsustainable, then its practices are not tenable in the long-term, and at some point in the future it will fall out of balance and burn up its resources.

The most stable cultures are sustainable (Inuit, !Kung San, Sami). Some unsustainable cultures become stable through might (The United States, most of the trading world). A culture that was stable (or could be stable) and sustainable can be acted upon by other cultures or natural forces, and their way of life can end (most aboriginal cultures have found themselves in a version of this predicament by now). And sometimes unstable and/or unsustainable cultures find their way to better practices and more security -- we see this usually on the small scale rather than the large and seems to occur most often when participants in a larger unstable and/or unsustainable culture purposefully take themselves out of the system to start anew. Often such experiments fail miserably; sometimes it seems to work well (Iceland works as both stable and sustainable, despite its financial problems; The Farm in Tennessee is doing alright; the Latin Settlement "Sisterdale" in Kendall County, Texas got really unstable really quickly when the Confederates murdered the Free Thinkers in 1862; etc.).

Even though there are many paths to get there, and even though cultures may find themselves moving in and out of them, there are just 4 ways for a culture to exist. Here's a graph:

4[edit | edit source]

Two Problems

Models are too simple. As models approach real life complexity, they lose their utility as tools to simplify matters. Reducing all of human activity to four fields is a very simple model indeed, and may be seen as laughable; but in as much as it is simple and it is true, it may be useful as a compass.

A very common problem is to idealize the ancient, the agrarian, the pastoral, as "pure". Morality gets conflated with economics: simple folks are praised as simply good. Modern, messy, complicated, stressed-out, post-colonial, information-age folks get lumped into some kind of loose and sloppy category of "bad". Reality is very different, and very much more complex, of course. This model doesn't ask for you to buy-in to the veneration of hunter-gatherers: hunter-gatherers commit murder too.

The Future

Despite such problems, the above model points us toward the 4th cell on the graph -- toward an ontology that values both stability and sustainability as the only reasonable direction for longterm cultural development. It is a conscious choice to move into stable and sustainable ways of life.

As we become aware that stability (security) is tied to economic sustainability (which is not necessarily the ability of an economy to grow forever or to metastasize precipitously, by the way), we can stack our affairs in such an order -- as individuals, as families, as towns, as nations -- that it may work to move our cultures into that 4th cell.

At the end of the day a comet could strike tomorrow. Life does gang aft agley. The onus is upon us to try, though. The responsibility to choose and to try is not avoidable.

Once we know the facts, as they say, doing nothing about them is also a choice.