Biofuel is a term used to describe fuel sources that are derived from easily regeneratable animal or plant-based resources. Biofuels are categorically different from fossil fuels, as biofuel production is not based on the anaerobic decomposition of buried organic matter. Furthermore, fossil fuel deposits take millions of year to form and are a naturally occurring phenomenon while resources for biofuel production are usually considered renewable and are typically representative of the bi-product from some other production process. Biofuels are thus a form of closed-loop recycling recycling, as the waste product from some production process is re-appropriated in to fuel for the process itself. It should be noted that although biofuels vary greatly in nature from fossil fuels, they are both a form of indirect solar energy; the initial energetic input stored in these fuels originated from the sun and was captured via terrestrial primary production processes, or photosynthesis.

Biofuels can be divided in to two categories of first-generation and second-generation:

- First generation describes biofuels that are derived from the edible parts of plants. A consideration associated with this form of biofuel is that large-scale production involves the mass cultivation of crops (such as maize) that could be otherwise be inputted into the global food system. Valuable resources such as arable land are thus prioritized for fuel production, rather than food production.

- Second generation describes biofuels that are derived from non-edible parts of plants, such as woody stems, branches, etc.[1] or from fruits that are not a part of the human diet. A benefit associated with second generation biofuels is that, unlike first generation processes, production is not inversely related to global food system production. Second-generation biofuel can be further divided in 2+ generation-biofuels and 2++ generation-biofuels

- 2+ generation-biofuel production involves no use of arable land at all for energy production (i.e. algae fuel)

- 2++ generation-biofuel production involves no use of arable land at all for energy production and no air pollution (this still occurs with the other biofuels, although there are no carbon emissions). (i.e. biohydrogen)

Background[edit | edit source]

Residual biomass can be re-appropriated without any primary treatment processes (i.e. the use of solid biomass) or be converted into various non-solid fuel forms; these forms are referred to as biogas and liquid biofuel. The purpose of such refinement processes is to improve the quality, specific energy content, transportability, etc., of the raw biomass source. It also allows for the capture of gases, which would otherwise be released in to the atmosphere, during natural biomass degradation processes. An example of this is the release of methane from anaerobic digestion in biomass waste or stockpiles.[2] These two forms of biofuel differ in there uses and applications; for example primary uses of biogas include cooking and lighting in a number of countries. On the other hand, development in liquid biofuel production has been driven by an ever-increasing societal need to displace fossil fuels as the default fuel source.

Within the context of acknowledged and growing anthropogenic impact on the global energy system, there has been notable movement towards cultivation of energy crops specifically for the production of biomass-derived fuel. These developments are taking place globally, across Europe, the United States as well as in several developing countries; as the human population continues to accelerate towards both complete extraction of fossil fuels, as well as catastrophic atmospheric CO2 levels, the need for integrated energy supply options has become increasingly overt. This need for supplementary and renewable fuel sources has thus catalyzed development of biofuel technology and will furthermore be the basis for which biomass re-appropriation will reach its full potential as an energy source.

In the following sections, a number of liquid biofuel forms will be outlined as well as their applications, and the conversion technologies used to derive them.

Environmental Considerations[edit | edit source]

There are two primary points of environmental concern, in relation to biomass-based energy derivation. The first point of concern is the potential for poor land management practices that are so often associated with any type fuel production. Examples of potential degrading production processes include large-scale implementation of mono-crops and the use of various chemical compounds to stimulate growth. Considerations specific to biofuel crop harvesting include the removal of plant residual material that would otherwise be broken down and increase the organic matter contentions and can furthermore contribute to greenhouse gas emissions through losses of soil carbon.[3]

However, land degradation and deforestation that could potentially be fostered by production of biofuels can be circumvented via cohesive and regulated land management policy. Furthermore, integration of non-conventional farming methodology, such as companion planting, IPM and conservation tillage into biofuel production policy could further reduce the potential for negative environmental impact associated with modern large-scale agricultural practices.

The second point of concern relates to the inversal nature of first generation fuel production and food production. This relationship was noted in the pervious sections. It arguable that such prioritization is not necessary, as much of the biomass requirement for energy production can be met through the re-appropriation of production bi-products (waste) or food industry residual material; you will remember that this form of biofuel is referred to as second generation. Policy infrastructure should thus be created with this consideration in mind, and limit the degree to which arable land and other production inputs can be employed for first generation biofuel production. Benefits to this limitation are two-fold, as it prevents undue stress on the environment related to biofuel production and restricts the degree to which this production can be prioritized over food production. For a more in depth outline of appropriate policy infrastructure, see.[4]

The use of crops that are native to the region can also provide part of the answer. In addition to this, the exact place (and the current use of the location -ie food production, CO2 already locked in the soil,...) where the crops are planted also matters. According to Wouter Achten of KU Leuven, biofuel-crops are best planted in CO2-poor soils and which are currently not used for agriculture. The first is for obvious reasons: by requiring the farmer to fertilise the soil with CO2 he locks away part of the CO2 in the atmosphere. The downside however is that extra fertilisation (and thus an increased cost) is required. The second is for less obvious reasons: if the land is used for agriculture, the crops that were planted need to be relocated. This could mean that there is an extra CO2-cost in transport (crops need to be transported further). This is known as ILUC.

Localised decentralised biofuel production from feedstock grown using sustainable agricultural practices been shown to offer part of a sustainable energy portfolio. A good example is for example rapeseed. This crop creates both biofuel (oil) as animal feed (the rest of the plant).

With the recent global call to reduce carbon dioxide emissions, there is a strong case for promoting the use of sustainable biomass-to-energy technologies worldwide. Using modern technology, enormous reductions can be made in carbon dioxide emissions, particularly if liquid biofuels are used to replace their fossil-based equivalents. In fact, if biomass energy production is done on a sustainable basis, there is little net carbon dioxide addition to the environment.

There are other environmental concerns related to each fuel that need to be kept in mind, such as toxic emissions and production of tars and soots.[5][6][7][8][9]

Advantages and disadvantages[edit | edit source]

Biofuels are not made from petroleum; not purchasing petroleum products allows you to avoid supporting business practices such as oil drilling that are harmful to the environment and human rights.

Pollution is any byproduct that cannot be fed back into the closed-end system. For biofuels (except for biohydrogen), this includes particulates and unburnt hydrocarbons (smoke), oxides of nitrogen, carbon monoxide, and a few others. These are typically much lower level than when fossil fuels are combusted, but they remain a problem, particularly for the human health (ie may cause respiratory problems, certain cancers,...).

Zero-emissions fuels do not have this problem, yet are more difficult to use in practice, and are also more expensive.

Note that what is pollution for one technology may be the biofuel in another. For example, if wood is heated anaerobically (with limited oxygen), it produces carbon monoxide, which is normally considered a pollutant, but if collected, can be burnt as a biofuel.[10]

Types of biofuel[edit | edit source]

First generation biofuels[edit | edit source]

'First-generation (or conventional) biofuels' are biofuels made from substances in crops (ie sugar, starch, and vegetable oil) that can be used for human consumption. Due to this, the production of fuel from these crops effectively creates problems in regards to the global food production.[11][12]

Solid biofuels[edit | edit source]

Solid biofuels are plant parts from crops grown for direct combustion. It includes wood, sawdust, grass trimmings, charcoal, agricultural waste, and dried manure. Some primary bio-energy feedstocks include industrial hemp, switchgrass and Miscanthus. They can be used as is or pressed into plates for easier incineration. Miscanthus or elephant grass generate a very high amount of dry matter.

1st generation bioalcohols[edit | edit source]

These include bioethanol, biomethanol and biobutanol. See Alcohols as fuel.

Biodiesel and green diesel[edit | edit source]

Biodiesel is a biofuel made from pure plant oil which has been treated with chemicals. An alternative approach for making biodiesel that does not involve the use of chemicals for the production also exists. This approach makes use of genetically modified organisms.[13][14] Biodiesel can be used in nearly any diesel engine, with little or no engine modifications. Unlike straight vegetable oilW, it can be used as fuel (new, or waste frying oil) in any engine.

Plant oils[edit | edit source]

Plant oil, which includes pure plant oil (PPO) and waste plant oil (WPO), can be used as a (bio)fuel. PPO is new plant oil whereas WPO is pure plant oil that has already been used for frying food. Plant oil is a very useful fuel as it uses plants as the source material. Plants are able to gather a huge amount of solar energy at a relatively low cost (due to the numbers in which they occur and the amount of space they can occupy). Note that PPO can be further divided in the First-generation and Second-generation fuel type. WPO is always a second-generation fuel.

Second generation biofuels[edit | edit source]

'Second generation biofuels' are biofuels produced from made from substances in crops (ie cellulose) that can not be used for human consumption. Unlike first generation biofuels they do not create problems in regards to the global food production.

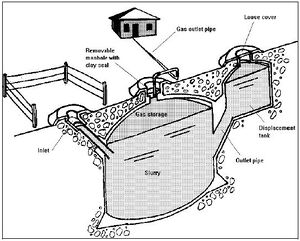

Biogas[edit | edit source]

See biogas

Syngas[edit | edit source]

Synthesis gas (or Syngas) is a gas mixture that contains varying amounts of hydrogen (H2), carbon monoxide (CO) and often some carbon dioxide (CO2) as well.

2nd generation bioalcohols[edit | edit source]

This includes ie biobutanol, biomethanol, bioethanol made from fruits,... from crops that are not suitable to human consumption (ie poisonous crops) as well as cellulosic ethanol (ethanol made from woody plant parts (non-consumable plant parts of humanly edible crops) Woody plant parts can be converted to ethanol yet at present (2007 D.C.) it is not yet a economicly viable method.[15]

Wood gas[edit | edit source]

This article deals around the use of wood gas in internal combustion engines. The process of biomass gasification is distinctly different from that of biogas production.

Algae fuel[edit | edit source]

Algae fuel, or algal fuel,[16] is a second-generation biofuel made from algae. Compared with other second generation biofuels, algae are relatively high-yield high-cost (30 times more energy per acre than terrestrial crops) feedstocks to produce biofuels. Since the whole organism converts sunlight into oil, algae can produce more oil in an area the size of a two-car garage than an entire football field of soybeans.[17]

Nowadays they cost $5–10/kg and there is active research to reduce both capital and operating costs of production so that it is commercially viable.[18][19][20] According to René Wijffels the current systems do not yet allow algae fuel to be produced competitively. However using new (closed) systems, and by scaling up the production it would be possible to reduce costs by 10X, upto a price of 0,4 € per kg of algae.[21]

Algae can potentially thrive on exhaust gases from power plants which run on fossil fuel (or any fuel that is burnt to product carbon dioxide. The algae grows faster thanks to the high concentration of carbon dioxide, which would otherwise be emitted as a greenhouse gas in the atmosphere, increasing climate change.

However, it does appear to have greater environmental impact than other forms of biofuel.[22]

Biohydrogen[edit | edit source]

Hydrogen can be used as fuel in both internal combustion engines as well as hydrogen fuel cells. It can be produced using a chemical process or a biological process (most commonly from waste organic materials -ie using algae, bacteria or archaea- )..[23]

DMF[edit | edit source]

2,5-Dimethylfuran is a heterocyclic compound with the formula (CH3)2C4H2O. Although often abbreviated DMF, it should not be confused with dimethylformamide. A derivative of furan, this simple compound is a potential biofuel, being derivable from cellulose.

BioDME[edit | edit source]

Dimethyl ether (DME; also known as methoxymethane) is the organic compound with the formula CH3OCH3, (sometimes ambiguously simplified to C2H6O as it is an isomer of ethanol). The simplest ether, it is a colorless gas that is a useful precursor to other organic compounds and an aerosol propellant that is currently being demonstrated for use in a variety of fuel applications.

Dimethyl ether was first synthesised by Jean-Baptiste Dumas and Eugene Péligot in 1835 by distillation of methanol and sulfuric acid.

Fischer-Tropsch diesel[edit | edit source]

Synthetic fuel or synfuel is a liquid fuel, or sometimes gaseous fuel, obtained from syngas, a mixture of carbon monoxide and hydrogen, in which the syngas was derived from gasification of solid feedstocks such as coal or biomass or by reforming of natural gas.

Common ways for refining synthetic fuels include the Fischer–Tropsch conversion, methanol to gasoline conversion, or direct coal liquefaction.

Biohydrogen diesel[edit | edit source]

Biohydrogen is H2 that is produced biologically. Interest is high in this technology because H2 is a clean fuel and can be readily produced from certain kinds of biomass, including biological waste. Furthermore some photosynthetic microorganisms are capable to produce H2 directly from water splitting using light as energy source.

Besides the promising possibilities of biological hydrogen production, many challenges characterize this technology. First challenges include those intrinsic to H2, such as storage and transportation of an explosive noncondensible gas. Additionally, hydrogen producing organisms are poisoned by O2 and yields of H2 are often low.

Mixed alcohols[edit | edit source]

The bioconversion of biomass to mixed alcohol fuels can be accomplished using the MixAlco process. Through bioconversion of biomass to a mixed alcohol fuel, more energy from the biomass will end up as liquid fuels than in converting biomass to ethanol by yeast fermentation.

The process involves a biological/chemical method for converting any biodegradable material (e.g., urban wastes, such as municipal solid waste, biodegradable waste, and sewage sludge, agricultural residues such as corn stover, sugarcane bagasse, cotton gin trash, manure) into useful chemicals, such as carboxylic acids (e.g., acetic, propionic, butyric acid), ketones (e.g., acetone, methyl ethyl ketone, diethyl ketone) and biofuels, such as a mixture of primary alcohols (e.g., ethanol, propanol, n-butanol) and/or a mixture of secondary alcohols (e.g., isopropanol, 2-butanol, 3-pentanol). Because of the many products that can be economically produced, this process is a true biorefinery.

Wood diesel[edit | edit source]

Wood diesel is a new biofuel developed by the University of Georgia from woodchips. In the process, oil is extracted and then added to unmodified diesel engines. In the process, either new plants are grown to be used in the process, or a new crop is planted to replace the harvested plants. The charcoal byproduct is put back into the soil as a fertilizer. According to the project's director, Tom Adams, since carbon is put back into the soil, this biofuel can actually be carbon negative not just carbon neutral. Carbon negative decreases carbon dioxide in the air reversing the greenhouse effect not just reducing it.

Use[edit | edit source]

With most biofuels the incompatibility with available engines provides an additional barrier to the adoption as reliable operation requires expensive engine modifications. 'Flexi-fuel' engines are available in some regions, commonly spark ignition engines able to run straight petrol(US-gas) or petrol/ethanol blends. Additives (bio ethers) can be applied to fuels to improve their performance.

Use in heat engines[edit | edit source]

It is possible to use biofuels in several heat engines, including internal combustion engines (diesel, gasoline) and Stirling engines. Reliability and performance of the engine will depend on:

- biofuel material compatibility - the compatability of fuel system and engine components to the fuel

- engine parameters: such as fuel delivery or spark timing, being optimised for the given fuel

- a suitable maintenance regime

Use in IC engines (diesel engines)[edit | edit source]

It is possible to use a wide range of liquid biofuels in a diesel engine, most commonly lipid based biofuels are used either in their pure form, plant oil, or transesterified as biodiesel. Diesel engine fuel delivery can be altered to suit the fuel. See also: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diesel_engine

Use in IC engines (gasoline engine)[edit | edit source]

Some liquid biofuels as ethanol can be used, oil-based biofuels can't be used though. Gases can also be used (ie wood gas (if filtered), biohydrogen, biogas and pure methane) See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internal_combustion_engine

Use in Stirling engines[edit | edit source]

Stirling engines can use a wide range of biofuels, both liquid biofuels (oils, ethanol,...), solid biofuels (ie wood, seeds,...) and gas-based biofuels (ie wood gas (if filtered), biohydrogen, biogas, pure methane)

Use in steam and fuel-powered turbines[edit | edit source]

Fuel-powered turbines can be run on liquid biofuels as oils, ethanol,... as well as some gas-based biofuels (ie biohydrogen, methane). Gas-based biofuels as wood gas and biogas are potentially also possible, but could give problems with fouling (due to tar,...) Steam turbines (bladed-rotor, Tesla,...) can run on all biofuels (solid, liquid, and gas-based biofuels). Fouling isn't a problem here (as opposed to fuel-powered turbines) as the heater chamber is generally separated from the chamber housing the turbine blades. Steam turbines however do require an additional energy conversion (fuel to steam) meaning there is some additional energy loss. The incineration of the fuel can btw be done using a pulse jet engine to increase efficiency, and to decrease fouling in this separate heating chamber (although it isn't a big problem) even more.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ also called cellulosic alcohol

- ↑ Methane and nitrous oxide emissions from biomass waste stockpiles. BTG biomass technology group BV, 2002.

- ↑ The State of Food and Agriculture. United Nations, 2008

- ↑ Negussie, A., Verbist, B.J.P. & Muys, B. (2014). Invasiveness prospects of Biofuels: avoid invasiveness threat of novel tropical biofuel crops. KLIMOS-Policy Brief 7, KLIMOS, Leuven.

- ↑ Anderson, T., Doig, A., Rees, D. and Khennas, S., Rural Energy Services: A handbook for sustainable energy development. ITDG Publishing, 1999.

- ↑ Ravindranath, N. H. and Hall, D. O., Biomass, Energy and the Environment: A Developing Country Perspective from India. Oxford University Press, 1995.

- ↑ Karekezi, S. and Ranja, T., Renewable Energy Technologies in Africa. AFREPEN, 1997.

- ↑ Kristoferson L. A., and Bokalders V., Renewable Energy Technologies - their application in developing countries. ITDG Publishing, 1991.

- ↑ Johansen, T.B. et al, Renewable Energy Sources for Fuels and Electricity. Island Press, Washington D.C., 1993.

- ↑ Biofuel

- ↑ Jean Ziegler calling first generation biofuels a crime against humanity

- ↑ Issues relating to first and some second generation biofuels

- ↑ Production of biodiesel without using chemicals

- ↑ Jay Keasling using GM microbes to produced biodiesel

- ↑ Cellulosic Ethanol: One Molecule Could Cure Our Addiction to Oil, Evan Ratliff, Wired Magazine October 24, 2007

- ↑ "Oilgae.com – Oil from Algae!". Retrieved 2008-06-10.

- ↑ "Why Algae?". Solix Biofuels. Retrieved 2008-06-11.

- ↑ Hartman, Eviana (2008-01-06). ""A Promising Oil Alternative: Algae Energy"". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2008-06-10.

- ↑ "{PhD thesis on algae production for bioenergy}" (PDF). Murdoch University, Western Australia. Retrieved 2008-06-10.

- ↑ ""Algal Oil Diesel, LLP"".

- ↑ EOS magazine, 6, 2012

- ↑ Engineers Find Significant Environmental Impacts with Algae-Based Biofuel

- ↑ Demirbas, A. (2009). Biohydrogen: For Future Engine Fuel Demands. Trabzon: Springer. ISBN 1-84882-510-2

External links[edit | edit source]

- Wikipedia:Biofuel

- Wikipedia:Renewable Natural Gas

- Open Biofuel Engine Development - Collaborative biofuel engine tuning

- Builtitsolar; has info on making some biofuels

- Biofuel Bay - Biofuel primer and educational resource

- Biofuel Debate Forum - Biofuel, Biodiesel and Bioenergy discussion forum

- Trade Association: American Biogas Council Subscribe to e-newsletter, American Biogas News