Carbon nanotubesW (CNT) have been placed at the forefront of materials technology since their discovery in the early 1990s. Extensive research has been conducted on them for just under two decades, revealing many desirable and unique mechanical, electrical, optical and electron transport properties. One of the areas that can still be greatly improved is the practical strength and mechanical properties of carbon nanotubes. For example the theoretical value of the tensile strength of CNTs is estimated to be between 140GPa to 177GPa. However due to defects in the material, only practical values of up to 63GPa have been achieved. Another major challenge of implementing carbon nanotubes has been the fabrication of functional macro-scale structures. It therefore can be seen that there is still a large potential for improvement in the mechanical material propertiesW of carbon nanotubes.

Please note that this page deals with the mechanical properties of carbon nanotubes and how to improve them, not how to improve the synthesis methods. For an in depth look at the different synthesis techniques of carbon nanotubes and how to improve them please view the page Synthesis of Carbon Nanotubes.

Mechanical Properties[edit | edit source]

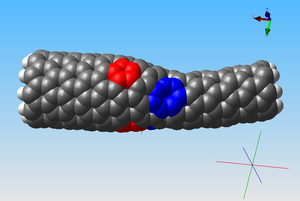

The mechanical properties of carbon nanotubes are defined by two main measurements, the Young's ModulusW and tensile strengthW (carbon nanotubes are respectively the stiffest and strongest materials yet to be discovered). CNTs are categorized into two different groups, single-walled CNTs and multi-walled CNTs this is because each of these groups has varying mechanical properties and failure mechanisms. The mechanical properties of all CNTs however, are a direct result of their unique bonding structure formed with orbital hybridizationW. Nanotubes are composed entirely of sp2 bonds, a bonding structure that is even stronger then the sp3 bonding structure found in diamonds. Conceptually carbon nanotubes are simply sheets of grapheneW rolled seamlessly to form a cylinder.[1] Theoretically the tensile strength and young's modulus of carbon nanotubes has been found to be upwards of ~140GPa and ~1TPa respectively.[2] While we have experimentally found the young's modulus to meet and even exceed the tera-pascal value no nanotube of any kind has been found to have a practical strength even close to that of the theoretical value. This is caused heavily by defects in the material.[1] Defects in the material can lower the tensile strength by values up to approximately 85%. It is commonly known that a chain is only as strong as its weakest link. This phenomena applies to CNTs, they are only as strong as their weakest segment.

Mechanically, it is also important to know that carbon nanotubes have a very low density around 1.3 to 1.4 g/cm3 depending on the type of CNT.[3] This means that they are also a very light material another desirable property in almost all situations. Not only that but the interesting kinetic energyW properties of nanotubes will make them even more valuable to mechanical engineers. Because these tubes are hollow they have an astonishing energy absorption property where the tubes bend elastically and convert kinetic energy into potential energy before they bend back to their original position. Multi-walled carbon nanotubes also exhibit a striking telescoping property where an interior nanotube may slide linearly or rotationally with almost zero friction.

Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes[edit | edit source]

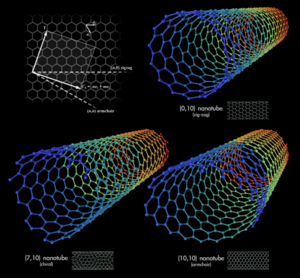

Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNT) have diameters of close to 1 nanometer. They are simply a one atom thick layer of graphite (graphene) wrapped into a seamless cylinder. The graphene sheets are represented by a pair of indices (n,m) called chiral vectors. The integers n and m denote the number of unit vectors in two directions (normally the vertical and horizontal planes) of the honeycomb crystal lattice of the graphene. The strongest nanotubes are called "armchair" nanotubes where n=m, the next strongest nanotube type is called "zigzag" and this is where m=0, and the rest are simply referred to has "chiral" nanotubes.

The most widely accepted experimental values of strength and modulus were found by Yu et al. in 2000 by doing stress-strain measurements on individual SWNTs inside an electron microscope. This experiment found modulus values in the range of 0.32 to 1.47 TPa and tensile strengths between 10 and 52 GPa. They were also able to observe that the failure mechanism in SWNTs was the splitting of the perimeter of the bundle only.[2]

Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes[edit | edit source]

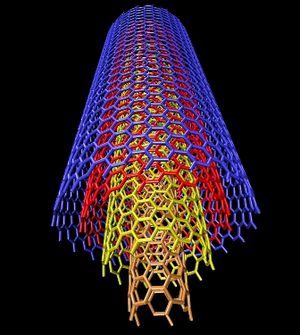

Multi-walled carbon nanotubes are known to have diameters between 2 and 100 nanometers. Conceptually they are just multiple sheets of graphene wrapped around each other forming multiple seamless cylinders inside around each other. Another way to visualize this is placing multiple single-walled carbon nanotubes inside each other. The properties of these nanotubes can differ significantly from SWNTs, the change most prominent in the electrical, thermal and chemical aspects.

The most widely accepted experimental values of strength and modulus were again found by Yu et al. in 2000 by doing stress-strain measurements on individual MWNTs inside an electron microscope. They found experimental modulus values in the range of 0.27 to 0.95 TPa and tensile strengths between 11 and 63 GPa. They were also able to observe that there is a "sword in sheath" failure mechanism in MWNTs. This is when the outer nanotube fails perpendicularly to tensile stress being applied. This causes a telescoping action where the outer wall pulls apart before the next layer begins to fail.[2]

Material Improvement Processes[edit | edit source]

The biggest problem with carbon nanotubes (disregarding that they are still expensive and in small quantities) is that they are extremely small and extremely hard to bond with each other. This means at the moment while they are extremely promising in nanoscience involving such things as transistors and other electrical, optical and thermal applications they are almost useless on the macroscopic level, which is what mechanical engineers primarily deal with. For example while a carbon nanotube may have a tensile strength of 63 GPa (more then a full order of magnitude above the strongest steel) the force needed for it to fail is much lower because its cross-section is so much smaller then conventional steel. To improve the practical values we can look at several different techniques, which improve different mechanical aspects of the carbon nanotube.

Defect Control[edit | edit source]

Conceptually crystallographic defectW control is the easiest improvement technique to understand. The strength and stiffness of a nanotube (which are debatably the most important mechanical properties of CNTs) are heavily reliant on the defect concentration and defect-defect interaction.[4] So it's simple, if we remove all of the defects in a carbon nanotube we will drastically improve the strength and young's modulus. Unfortunately it's not that easy, most defects are created during synthesis and at random due to the atmosphere, pressure and temperature during formation.[3] Not only that but the most promising industrial synthesizing technique, chemical vapour deposition (CVD) uses catalytic methods which increases disorder and the number defects. This means that while CVD is able to produce many more nanotubes at a higher efficiency it produces tubes of lower mechanical quality.[3] Some research has been conducted into CVD without a catalyst however they require post-processing and still do not produce nanotubes to the same quality as Laser Ablation and Arc Discharge synthesis methods.

Several types of defects can be seen the link below, in this article they are looking at connecting carbon nanotubes with pair defects

Connecting carbon nanotubes with pentagon-heptagon pair defects

Intercalation[edit | edit source]

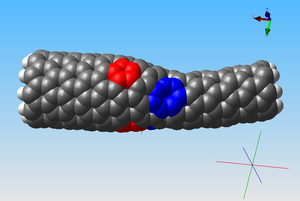

Low-bulk mechanical properties of carbon nanotubes are partly due to bundles of 10-50nm diameter that are only weakly bound by van der Waals interactions at junction points. Because of this it is hard to apply them macroscopically. To apply this to a macroscopic level CNTs have been used as reinforcing agents in polymers and composites for several years. Ideally, any load applied to the outside polymer or composite matrix is transferred to tensile stress in the nanotubes. This method has increased the Young's Modulus by factors of 1.8 and 3.5 for MWCNTs and SWCNTs respectively. Recently however it has been proven that the reverse procedure of polymer intercalation can improve the properties of the bulk CNT material. The polymer-intercalated material has been shown to have improvements in the Young's Modulus and tensile strength by factors of ~3 and ~9 respectively.[5] The nature of this reinforcement is thought to be caused by the nanotubes being interlaced by the polymer strands. The polymer grows on the inside and outside of the nanotube and then polymer transfers the stress from one nanotube to the next. This extra reinforcement at the junction plays a large role on the macroscopic scale.[5]

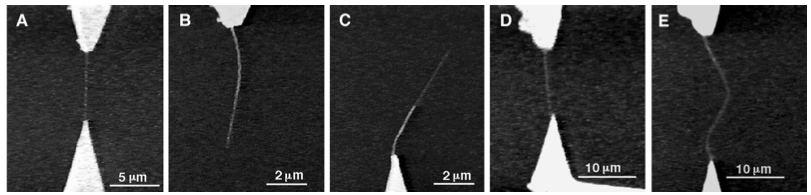

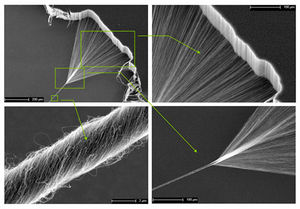

Yarning[edit | edit source]

Carbon nanotube yarning is debatably the biggest breakthrough in the past 5 years to improve the macroscopic properties of CNTs. It provides amazing energy enhancements. By spinning the nanotubes together you can increase the overall thickness, giving the nanotubes a larger impulse meaning that they can absorb more energy. This is huge breakthrough for kinetic applications such as bulletproof armor. It also allows you to make a macrostructure completely of nanotubes meaning that you can retain low density and high strength. The spinning process is not conceptually difficultly to understand, as it is the same as normal yarning (spinning small fibers into larger ones). The hard part is applying it to such a small scale without the tubes getting tangled and intertwined. Many researchers are still exploiting ways to 'fine tune' the process to yield even better strength, structure and productivity.[6]

CSIRO a company in Australia is a pioneer in this field and has had great success with creating high quality carbon nanotube yarns, please go to there website below to learn more about there innovative techniques and watch their videos on their spinning process:

CSIRO Carbon Nanotube Yarn

Spinning Carbon Nanotubes Video

Annealing[edit | edit source]

Annealing is a used to as a method of eliminating defects however unlike defect control, the annealing is applied after the bulk material has already been fabricated to try and remove some of the defects created during synthesis. This method is normally used on nanotubes created by CVD, however you can apply it to any type of nanotube. It is most commonly used after CVD to try and improve the properties of the lower quality nanotubes created by CVD. The annealing process will allow the removal of lattice defects proportionally to the annealing temperature and time.[7]

Mechanical Applications[edit | edit source]

The potential applications of this phenomenal material are truly endless. They can be used to improve the properties in almost any engineering situation.

Structural[edit | edit source]

- Space Elevator: Carbon Nanotubes could be used as the cable in an elevators to space

- Reinforced Composite Materials: We can improve the tensile strength of composite materials by placing nanotubes within the material

- Aerospace: Super strong light weight carbon nanotube paper could be used as the outer shell of an aircraft

Energy[edit | edit source]

- Bearings: The friction coefficient between the nanotubes nested within each other in multi-walled carbon nanotubes is effectively zero, this means we could create rotation bearing the effectively will never lose energy

- Flywheels:A flywheel made of carbon nanotubes could potentially store energy at a density approaching that of conventional fossil fuels. Since energy can be added to and removed from flywheels very efficiently in the form of electricity, this might offer a way of storing electricity.

- Bulletproof Armour: 0.6mm of carbon nanotubes can completely stop a bullet. They are also much lighter then conventional armour such as kevlar and ceramic plates.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Coleman,Jonathan N.; Khan,Umar; Blau,Werner J.; Gun'ko,Yurii K. Small but strong: A review of the mechanical properties of carbon nanotube–polymer composites, Carbon, 2006, 44, 9, 1624-1652

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Min-Feng Yu, Oleg Lourie, Mark J. Dyer, Katerina Moloni, Thomas F. Kelly, Rodney S. Ruoff; Strength and Breaking Mechanism of Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes Under Tensile Load; 28 JANUARY 2000, VOL 287 SCIENCE, www.sciencemag.org

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 J.-P. Salvetat∗, J.-M. Bonard, N.H. Thomson, A.J. Kulik, L. Forro ́, W. Benoit, L. Zuppiroli, Mechanical properties of carbon nanotubes; Received: 17 May 1999/Accepted: 18 May 1999/Published online: 29 July 1999

- ↑ C. Shet, N. Chandra, and S. Namilae; Defect-Defect Interaction in Carbon Nanotubes under Mechanical Loading; Mechanics of Advanced Mateiiah and Struciuies. 12: 55-65.2005 Copyrighl © Tiylor & Francis Inc. ISSN: I.S37-6494 print/1537-6532 online DOf: 10.108O/1537649049CM92089

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Coleman,Jonathan N.; Blau,Werner J.; Dalton,Alan B, Munoz,Edgar; Collins,Steve; Kim,Bog G.; Razal,Joselito; Selvidge,Miles; Vieiro,Guillermo; Baughman,Ray H; Improving the mechanical properties of single-walled carbon nanotube sheets by intercalation of polymeric adhesives; Appl.Phys.Lett., 2003, 82, 11, 1682-1684, AIP

- ↑ Tran,C.D.; Humphries,W.; Smith,S.M.; Huynh,C.; Lucas,S.; Improving the tensile strength of carbon nanotube spun yarns using a modified spinning process; Carbon, 2009, 47, 11, 2662-2670

- ↑ S. Musso, M. Giorcelli, M. Pavese, S. Bianca, M. Rovere, A. Tagliaferro; Improving macroscopic physical and mechanical properties of thick layers of aligned multiwall carbon nanotubes by annealing treatment; Available online 3 December 2007