Coppicing

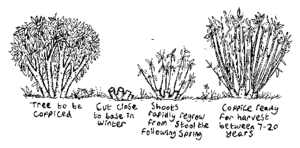

Coppicing is a traditional method of woodland management, by which young tree stems are cut down to a low level (usually about 0.3 meters / 1 foot from the ground), or sometimes right down to the ground. In subsequent growth years, many new shoots or "suckers" will grow up, and after a number of years the cycle begins again and the coppiced tree or stool is ready to be harvested again. Typically a coppice woodland is harvested in sections, on a rotation. In this way, a crop is available every year. This also has the side-effect of providing a rich variety of habitats, as the woodland always has a range of different aged stools growing in it. This is beneficial for biodiversity.

Coppicing can be thought of as the most intensive way of pruning a woody plant. The harvest point is at ground level. A related technique is pollarding, where the harvest point is located higher from the ground, in the canopy of the tree. Coppice is a more severe disturbance to the tree than pollarding. Coppicing is a deliberate act carried out by humans. Damage from weather events or from animals other than humans is not coppicing.

Coppicing is generally done during the dormant season (late winter or early spring in temperate climates), when the plant is not growing. In this way, at the beginning of the next growing season, the plant will be able to rapidly recover.

Related terms[edit | edit source]

- Coppicing is cutting a tree at a height of about 0.3 meters from the ground.

- Pollarding in the traditional sense is cutting a tree at a height of about 2 meters of the ground. In the modern urban context, it often refers to reducing a tree to the main trunk and several main branches, leaving the tree at about 10-15 meters. It is a repeated process every few years.

- "Topping" is a tree surgery term. It is a single procedure which can kill a tree. It means reducing a mature tree to the main trunk. It is a cheaper alternative to removal.

- "Canopy reduction" is reduction of the length of a branch, or reduction in the number of branches.

Plants[edit | edit source]

Generally speaking, any broad leaf tree species can be coppiced. Several examples are listed in other parts of this article. For example, Hazel is a very common tree to be used in coppice systems. Willows and mulberry can easily cope with coppicing and pollarding. However, not all woody plants will coppice well, for example most conifers. A lot of softwood species do not coppice well, for example beech.

The cycle length depends upon the species cut, the local custom, and the use to which the product is put. Birch can be coppiced for faggots on a 3 or 4 year cycle, whereas oak can be coppiced over a 50-year cycle for poles or firewood.

In the first growing season after coppice, there is rapid growth of many shoots 1.8 - 3 meter (6-8 feet) tall, which have minimal side branches. This rapid growth is because the plant is in shock from the coppicing event. After all, when a tree looses all of it's leaf bearing branches, it can no long photosynthesize. So an "emergency response" is triggered by the plant in order to survive. Older trees generally respond less vigorously to coppicing than younger trees.

Another potential problem with coppicing is that animals can reach the new growth and eat it. In pollarding the height of the fresh growth is out of reach of most animals.

Uses[edit | edit source]

Young shoots may be used for interweaving in wattle fencing, as is the practice with willows.

Mature shoots may be used as large poles, as was often the custom with hardwood such as oaks or ashes. This practice creates long, straight poles (pole wood), which are better for working than naturally grown trees which have bends and forks. One classic use for such poles is bean poles.

Coppicing may also be practiced to encourage specific growth patterns, as with cinnamon trees which are grown for their bark. Coppice can also be used for animal fodder.

Other uses include:

- Firewood

- Coppice generates excellent material for basket weaving because the shoots are very uniform.

History[edit | edit source]

In the carefully managed woodland of the past, trees were a crop. Coppicing developed as a faster method of harvesting wood compared to killing the tree each time it was harvested. In the latter process, a new tree must be replanted and regrow from a seedling, establish itself and reach the harvestable size. This is a much longer process than coppicing a tree, which preserves the roots. The energy stored in the roots can rapidly regrow after coppicing. Pollarding was developed so that animals (cows, deer, horses, etc.) could not reach the new growth and eat it.

Traditional tree systems throughout Europe in the middle ages often took the form of "coppice with standards". The standard trees were allowed to grow to full size. They were the property of the land owner. These trees were used for lumber. Often, these trees were chosen to provide secondary food for livestock, such as beech, chestnut or oak. These trees were cut on a 70-100 year cycle. The density of these trees was about 1-10 per acre, which is a spacing of about 20 meters (65 foot) between trees, on center. Grown in between the standards were coppice trees. Commoners had rights to use this renewable resource. The spacing of coppice trees was about 1.8-3 meters (6-10 feet) between stools.

In Europe coppiced hardwoods were extensively used in shipbuilding (wooden ships) or carriage building.

In Southern Britain, coppice was traditionally hazel, grown amongst oak standards (large trees). This provided wood for many purposes, especially charcoal which before the availability of coal was economically significant in allowing smelting of metals.

Current practice[edit | edit source]

There are very small amounts of hardwood coppices grown in Europe, for making wooden buildings and furniture.

In Southern Britain, a minority of these woods are still operated for coppice today, often by conservation organizations, producing material for hurdle-making, thatching spars, local charcoal-burning or other crafts. The only remaining large-scale commercial coppice crop in the area is sweet chestnut which is grown in parts of East Sussex and Kent for splitting and binding into cleft chestnut paling fence bound together with wire.

Pollarding in the modern urban context has a slightly different meaning. Due to lack of competition from other trees, trees planted along avenues and roads tend to grow very large. This can create problems with overhead cables, and reduce light for residences. Such trees are often pollarded at a higher level (10-15 meters from the ground) than pollarding in the traditional sense. This type of pollarding is closer to a reduction, where the canopy is made smaller, but in pollarding all the leaves are lost, leaving a bare trunk and a skeleton of main branches. When this cycle is repeated many times, the structure of the tree is very resilient to high winds. This type of pollarding is also carried out for aesthetic reasons, to create a desired shape of tree, or as an alternative to removing a tree which has grown too large.

-

A recently coppiced alder stool in Hampshire

-

The same alder stool after one year's regrowth

See also[edit | edit source]

- Pruning fruit trees

- Pollarding

- Shredding

- Apical dominance