Composite materialsW in the Aircraft Industry and have allowed engineers to overcome obstacles that have been met when using the materials individually. The constituent materials retain their identities in the composites and do not dissolve or otherwise merge completely into each other. Together, the materials create a 'hybrid' material that has improved structural properties.

The development of light-weight, high-temperature resistant composite materials will allow the next generation of high-performance, economical aircraft designs to materialize. Usage of such materials will reduce fuel consumption, improve efficiency and reduce direct operating costs of aircraft.

Composite materials can be formed into various shapes and, if desired, the fibres can be wound tightly to increase strength. A useful feature of composites is that they can be layered, with the fibres in each layer running in a different direction. This allows an engineer to design structures with unique properties. For example, a structure can be designed so that it will bend in one direction, but not another.[2]

Synthesis of basic composites[edit | edit source]

In a basic composite, one material acts as a supporting matrix, while another material builds on this base scaffolding and reinforces the entire material. Formation of the material can be an expensive and complex process. In essence, a base material matrix is laid out in a mould under high temperature and pressure. An epoxy or resin is then poured over the base material, creating a strong material when the composite material is cooled. The composite can also be produced by embedding fibres of a secondary material into the base matrix.

Composites have good tensile strength and resistance to compression, making them suitable for use in aircraft part manufacture. The tensile strength of the material comes from its fibrous nature. When a tensile force is applied, the fibres within the composite line up with the direction of the applied force, giving its tensile strength. The good resistance to compression can be attributed to the adhesive and stiffness properties of the base matrix system. It is the role of the resin to maintain the fibres as straight columns and to prevent them from buckling.

Aviation and composites[edit | edit source]

Composite materials are important to the Aviation Industry because they provide structural strength comparable to metallic alloys, but at a lighter weight. This leads to improved fuel efficiency and performance from an aircraft.[3][4]

The role of composites in the aviation industry[edit | edit source]

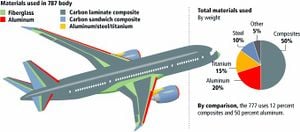

Fibreglass is the most common composite material, and consists of glass fibres embedded in a resin matrix. Fibreglass was first used widely in the 1950s for boats and automobiles. Fibreglass was first used in the Boeing 707 passenger jet in the 1950s, where it comprised about two percent of the structure. Each generation of new aircraft built by Boeing had an increased percentage of composite material usage; the highest being 50% composite usage in the 787 Dreamliner.

The Boeing 787 Dreamliner will be the first commercial aircraft in which major structural elements are made of composite materials rather than aluminum alloys.[1] There will be a shift away from archaic fibreglass composites to more advanced carbon laminate and carbon sandwich composites in this aircraft. Problems have been encountered with the Dreamliner's wing box, which have been attributed to insufficient stiffness in the composite materials used to build the part.[1] This has lead to delays in the initial delivery dates of the aircraft. In order to resolve these problems, Boeing is stiffening the wing boxes by adding new brackets to wing boxes already built, while modifying wing boxes that are yet to be built.[1]

Testing of composite materials[edit | edit source]

It has been found difficult to accurately model the performance of a composite-made part by computer simulation due to the complex nature of the material. Composites are often layered on top of each other for added strength, but this complicates the pre-manufacture testing phase, as the layers are oriented in different directions, making it difficult to predict how they will behave when tested.[1]

Mechanical stress tests can also be performed on the parts. These tests start with small scale models, then move on to progressively larger parts of the structure, and finally to the full structure. The structural parts are put into hydraulic machines that bend and twist them to mimic stresses that go far beyond worst-expected conditions in real flights.

Factors of composite material usage[edit | edit source]

Weight reduction is the greatest advantage of composite material usage and is one of the key factors in decisions regarding its selection. Other advantages include its high corrosion resistance and its resistance to damage from fatigue. These factors play a role in reducing operating costs of the aircraft in the long run, further improving its efficiency. Composites have the advantage that they can be formed into almost any shape using the moulding process, but this compounds the already difficult modelling problem.

A major disadvantage about use of composites is that they are a relatively new material, and as such have a high cost. The high cost is also attributed to the labour intensive and often complex fabrication process. Composites are hard to inspect for flaws, while some of them absorb moisture.

Even though it is heavier, aluminum, by contrast, is easy to manufacture and repair. It can be dented or punctured and still hold together. Composites are not like this; if they are damaged, they require immediate repair, which is difficult and expensive.

Fuel savings with reduced weight[edit | edit source]

Fuel consumption depends on several variables, including: dry aircraft weight, payload weight, age of aircraft, quality of fuel, air speed, weather, among other things. The weight of aircraft components made of composite materials are reduced by approximately 20%, such as in the case of the 787 Dreamliner.[4]

A sample calculation of total fuel savings with a 20% empty weight reduction will be done below for an Airbus A340-300 aircraft.

Initial sample values for this case study were obtained from an external source.[5]

Given:

- Operating Empty Weight (OEW): 129,300kg

- Maximum Zero Fuel Weight (MZFW): 178,000kg

- Maximum Take-Off Weight (MTOW): 275,000kg

- Max. Range @ Max. Weight: 10,458km

Other quantities can be calculated from the above given figures:

- Maximum Cargo Weight = MZFW - OEW = 48,700kg

- Maximum Fuel Weight = MTOW - MZFW = 97,000kg

So, we can further calculate the fuel consumption in kg/km based on maximum fuel weight and maximum range = 97,000kg/10,458km = 9.275kg/km

Following is the calculation for anticipated fuel savings with a 20% weight reduction, which will only reduce the OEW value by 20%:

- OEW(new) = 129,300kg * 0.8 = 103,440kg, which equates to a 25,860kg weight saving.

Assuming that cargo and fuel weight remain constant:

- MZFW(new) = MZFW - 25,680kg = 152,320kg

- MTOW(new) = MTOW - 25,680kg = 249,320kg

The 97,000kg mass of fuel has a reduced MTOW to deal with, and thus will have increased range because maximum weight and maximum range are inversely proportional quantities.

Using simples ratios to calculate the new range:

Solving for X gives a new range of:

- X = 11,535.18km

This gives a new value for fuel consumption with reduced weight = 97,000kg/11,535.18km = 8.409kg/km

To put this in perspective, over a 10,000km journey, there will be an approximate fuel saving of 8,660kg with a 20% reduction of empty weight.

Environmental impact[edit | edit source]

There is a shift developing more prominently towards Green Engineering. Our environment is given increased thought and attention by today's society. This is true for composite material manufacture as well.

As mentioned previously, composites have a lighter weight and similar strength values as heavier materials. When the lighter composite is transported, or is used in a transport application, there is a lower environmental load compared to the heavier alternatives. Composites are also more corrosion-resistant than metallic based materials, which means that parts will last longer.[7] These factors combine to make composites good alternate materials from an environmental perspective.

Conventionally produced composite materials are made from petroleum based fibres and resins, and are non-biodegradable by nature.[8] This presents a significant problem as most composites end up in a landfill once the life cycle of a composite comes to an end.[8] There is significant research being conducted in biodegradable composites which are made from natural fibres.[9] The discovery of biodegradable composite materials that can be easily manufactured on a large-scale and have properties similar to conventional composites will revolutionize several industries, including the aviation industry.

An alternative option to aid environmental efforts would be to recycle used parts from decommissioned aircraft. The 'unengineering' of an aircraft is a complex and expensive process, but may save companies money due to the high cost of purchasing first-hand parts.[6]

Future composite materials[edit | edit source]

Ceramic matrix composites[edit | edit source]

Major efforts are underway to develop light-weight, high-temperature composite materials at National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) for use in aircraft parts. Temperatures as high as 1650°C are anticipated for the turbine inlets of a conceptual engine based on preliminary calculations.[3] In order for materials to withstand such temperatures, the use of Ceramic Matrix Composites (CMCs) is required. The use of CMCs in advanced engines will also allow an increase in the temperature at which the engine can be operated, leading to increased yield.[10] Although CMCs are promising structural materials, their applications are limited due to lack of suitable reinforcement materials, processing difficulties, lifetime and cost.

Spider silk fibres[edit | edit source]

Spider silk is another promising material for composite material usage. Spider silk exhibits high ductility, allowing stretching of a fibre up to 140% of its normal length.[11] Spider silk also holds its strength at temperatures as low as -40°C.[11] These properties make spider silk ideal for use as a fibre material in the production of ductile composite materials that will retain their strength even at abnormal temperatures. Ductile composite materials will be beneficial to an aircraft in parts that will be subject to variable stresses, such as the joining of a wing with the main fuselage. The increased strength, toughness and ductility of such a composite will allow greater stresses to be applied to the part or joining before catastrophic failure occurs. Synthetic spider silk based composites will also have the advantage that their fibres will be biodegradable.

Many unsuccessful attempts have been made at reproducing spider silk in a laboratory, but perfect re-synthesis has not yet been achieved.[12]

Hybrid composite steel sheets[edit | edit source]

Another promising material can be stainless steel constructed with inspiration from composites and nanontech-fibres and plywood. The sheets of steel is made of same material and is able to handle and tool exactly the same way as conventional steel. But is some percent lighter for the same strengths. This is especially valuable for vehicle manufacturing. Patent pending, swedish company Lamera is a spinoff from research within Volvo Industries.

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

Due to their higher strength-to-weight ratios, composite materials have an advantage over conventional metallic materials; although, currently it is expensive to fabricate composites. Until techniques are introduced to reduce initial implementation costs and address the issue of non-biodegradability of current composites, this relatively new material will not be able to completely replace traditional metallic alloys.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Surface Modelling for Composite Materials - SIAG GD - Retrieved at http://www.ifi.uio.no/siag/problems/grandine/

- ↑ A to Z of Materials - Composites: A Basic Introduction - Retrieved at http://web.archive.org/web/20080806113558/http://www.azom.com/details.asp?ArticleID=962

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 INI International - Key to Metals - Retrieved at http://www.keytometals.com/Article103.htm

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Boeing's 787 Dreamliner Has a Composite Problem - Zimbio - Retrieved at http://web.archive.org/web/20101002101128/http://www.zimbio.com:80/Boeing+787+Dreamliner/articles/18/Boeing+787+Dreamliner+composite+problem

- ↑ Peeters, P.M. et al. - Fuel efficiency of commercial aircraft (pg. 16) - Retrieved at http://www.transportenvironment.org/docs/Publications/2005pubs/2005-12_nlr_aviation_fuel_efficiency.pdf

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 National Geographic Channel - Man Made: Plane - Retrieved from http://channel.nationalgeographic.com/series/man-made/3319/Photos#tab-Videos/05301 00

- ↑ A study of the environmental impact of composites - Retrieved at http://web.archive.org/web/20060923103650/http://www.plastkemiforetagen.se/Publikationer/PDF/Composite_materials_in_an_environmental_perspective.pdf

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Textile Insight - Green Textile Composites - Retrieved at http://www.textileinsight.com/articles.php?id=453

- ↑ A to Z of Materials - High Performance Composite Materials Produced from Biodegradable Natural Fibre Reinforced Plastics - Retrieved at http://www.azom.com/news.asp?newsID=13735

- ↑ R. Naslain - Universite Bordeaux - Ceramic Matrix Composites - Retrieved at http://web.archive.org/web/20101122114453/http://www.mpg.de/pdf/europeanWhiteBook/wb_materials_213_216.pdf

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Department of Chemistry - University of Bristol - Retrieved at http://www.chm.bris.ac.uk/motm/spider/page2.htm

- ↑ Wired Science - Spiders Make Golden Silk - Retrieved at http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2009/09/spider-silk/