Charcoal production

This article deals about the production of charcoal. There are several methods for processing wood residues to make them cleaner and easier to use as well as easier to transport. Production of charcoal is the most common.

It is worth mentioning at this point that the conversion of woodfuel to charcoal does not increase the energy content of the fuel - in fact the energy content is decreased. Charcoal is often produced in rural areas and transported for use in urban areas.

Overview[edit | edit source]

The pyrolysis temperature appears to be a critical factor determining char yield vs. energy yield (tradeoff). Flexi-pyrolysis units are being developed that can be set for either char yield or gasification yield. Dry biomass can be pyrolyzed at regular atmospheric pressure. For wet biomass, pyrolysis at higher pressure ("supercritical") may be necessary, requiring a more sophisticated technical set-up.

When large chunks of wood are used as feedstock, the charcoal may need to be crushed before use (beware: coal dust explosion !). Many agrigultural feedstocks and leaf litter will not need to be pulverized but will readily break into smaller pieces by themselves. For information on small-scale gardening, please consult the Gardening with Biochar FAQ, an excellent resource.

Kilns used[edit | edit source]

Charcoal can be made using various types of kilns.

Using traditional kilns[edit | edit source]

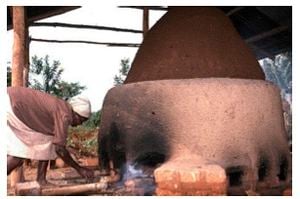

The process can be described by considering the combustion process discussed above. The wood is heated in the absence of sufficient oxygen which means that full combustion does not occur. This allows pyrolysis to take place, driving off the volatile gases and leaving the carbon or charcoal remaining. The removal of the moisture means that the charcoal has a much higher specific energy content than wood. Other biomass residues such as millet stems or corncobs can also be converted to charcoal.

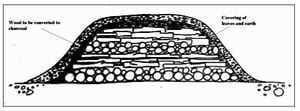

Charcoal is produced in a kiln or pit. A typical traditional earth kiln (see image 1) will comprise the fuel to be carbonised, which is stacked in a pile and covered with a layer of leaves and earth. Once the combustion process is underway the kiln is sealed, and then only once process is complete and cooling has taken place can the charcoal be removed.

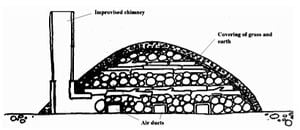

A simple improvement to the traditional kiln is also shown in image 3. A chimney and air ducts have been introduced which allow for a sophisticated gas and heat circulation system and with very little capital investment a significant increase in yield is achieved.

Using a clamp[edit | edit source]

The traditional method in Britain used a clamp which is itself already a relatively advanced yet locally-constructable kiln. This is essentially a pile of wooden logs (e.g. seasoned oak) leaning against a chimney (logs are placed in a circle). The chimney consists of 4 wooden stakes held up by some rope. The logs are completely covered with soil & straw allowing no air to enter. It has to be lit by introducing some burning fuel into the chimney; the logs burn very slowly (cold fire) and transform into charcoal in a period of 5 days burning. If the soil covering gets torn (cracked) due to the fire, additional soil is placed on the cracks. Once the burn is complete, the chimney is plugged to prevent air to enter.[3] Modern methods use a sealed metal container, as this does not have to be watched lest fire break through the covering.

Using charcoal kilns[edit | edit source]

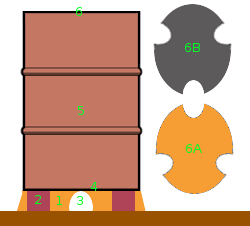

Several (relatively inexpensive) charcoal kilns can be made which can be used to make charcoal/ See the designs at Biochar-international page 1 and page 2 Most of these require at least some parts which can not be found in a natural environment (ie metal parts). On the upside however, such parts typically last longer and may be more efficient. Some very simple designs also exist consisting of only a few metal parts (ie 2 barrels), see NASA Langley Research Center's low-tech kiln