Solar hot water describes active and passive solar technologies that utilize the freely abundant solar thermal energy in order to heat water for a desired application.

It is one of the most efficient ways to heat water (in terms of energy/waste), as it requires no energy conversion, unlike electric-resistance heating or fuel burning. It is a simple transfer and concentration of heat energy from one place to another. (See Wikipedia:Heat transfer.) Another example of this technology's efficiency is it runs on solar energy, which is free, and only dependent on the technology used, and its cost and efficiency. In other words, the energy is free, only the collection, conversion, and storage devices contribute to the cost of the system. That being said, the main disadvantage of solar thermal energy is that it is only available wherever/whenever the Sun is visible.

If you have ever felt hot water trickle out of a garden hose that has been sitting in the sun, you’ve experienced solar hot water in action.

Essentially, a solar hot water system is made up of a solar thermal collector, a well-insulated storage container, and a system for transferring the heat from the collector to the container vis-à-vis a fluid medium, which in some cases is the water itself.

Applications[edit | edit source]

Being as there are countless applications using domestic, commercial, and industrial hot water globally, there are opportunities to apply solar thermal technologies to heat this water.

Today the market is changing and both the economic and environmental costs associated with using gas and electricity to heat water are being challenged by more efficient, less costly systems like the solar hot water system.

Background[edit | edit source]

Solar hot water is not a new phenomena. It was widely used in the United States up into about the 1920's when it was displaced by reliable fossil fuel systems.

Hot water is considered by some to have little application in the field of appropriate technology and to mostly be a luxury afforded by the developed world. One text[verification needed] on the subject suggests that what hot water is needed in the "3rd World" can be heated using a fuel such as wood that simultaneously heats the home and water. Such dismissals are dangerous on two counts:

- First, Appropriate Technology aims to reduce waste and increase efficiency in use of natural resources, while wood does heat both water and the home, it is also a natural resource not available in many impoverished countries. Whereas the sun is present everywhere and will be sending out energy regardless of whether we use it. Many women and children in 3rd world countries die of lung disease caused by incorrect ventilation and excess smoke from cooking fires, it actually tends to be the number 1 killer above aids and starvation.

- Second, It is imperative that where there is a need for hot water, there is a way to get that hot water cost-effectively and within the parameters set by the local resources. This technology, if spread, could cause a significant reduction in the size of a regions ecological footprint associated with conventional means of heating water.

Energy from the Sun[edit | edit source]

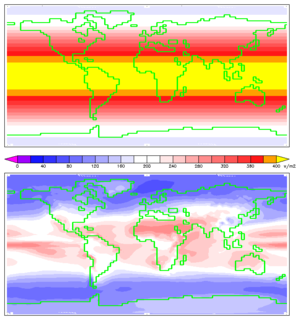

Solar radiation reaches the Earth's upper atmosphere at a rate of 1366 watts per square meter (W/m2).[1] Map A shows how the solar energy varies in different latitudes.

While traveling through the atmosphere, 6% of the incoming solar radiation (insolation) is reflected and 16% is absorbed resulting in a peak irradiance at the equator of 1,020 W/m². Average atmospheric conditions (clouds, dust, pollutants) further reduce insolation by 20% through reflection and 3% through absorption. Atmospheric conditions not only reduce the quantity of insolation reaching the Earth's surface but also affect the quality of insolation by diffusing incoming light and altering its spectrum.[2]

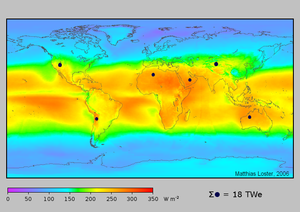

Map C shows the average global irradiance calculated from satellite data collected from 1991 to 1993. For example, in North America the average insolation at ground level over an entire year (including nights and periods of cloudy weather) lies between 125 and 375 W/m² (3 to 9 kWh/m²/day).[3] This represents the available power, and not the delivered power. At present, photovoltaic panels typically convert about 15% of incident sunlight into electricity; therefore, a solar panel in the contiguous United States on average delivers 19 to 56 W/m² or 0.45 - 1.35 kWh/m²/day.[4]

The dark disks in Map C on the right are an example of the land areas that, if covered with 8% efficient solar panels, would produce slightly more energy in the form of electricity than the total world primary energy supply in 2003..[5] While average insolation and power offer insight into solar power's potential on a regional scale, locally relevant conditions are of primary importance to the potential of a specific site.

After passing through the Earth's atmosphere, most of the sun's energy is in the form of visible and infrared radiation. Plants use solar energy to create chemical energy through photosynthesis. Humans regularly use this energy burning wood or fossil fuels, or when simply eating the plants, imagine if we found a way to harness this energy leaving plants and fossil fuels out of the equation.

A recent concern is global dimming, an effect of pollution that is allowing less sunlight to reach the Earth's surface. It is intricately linked with pollution particles and global warming, and it is mostly of concern for issues of global climate change, but is also of concern to proponents of solar power because of the existing and potential future decreases in available solar energy. (About 4% less solar energy is available at sea level over the timeframe of 1961–90,) mostly from increased reflection from clouds back into space.[6]

- Note: the Wikipedia content applies to this section only.

Types[edit | edit source]

Solar hot water systems are designed to transfer the sun's solar energy to water. Finding the most efficient and effective solar hot water system for a given situation can be a challenging task. There are a number of key factors that need to be considered when choosing the most appropriate system configuration. These factors include, to a large extent, amount of solar insolation, climate, construction, installation and materials costs, location and accessibility of the system, amount of water needing heating, frequency of hot water use, availability of electricity, availability of materials, and skill level in construction.

The following classifications of systems are in three groups of two and one group of one unique system. These four main groups are:

- Open loop vs Closed loop.

- Active vs Passive.

- Uses a heat exchanger vs Does not use a heat exchanger.

- Batch system.

Any given system uses one characteristic from each group. For example, a system may be an active, open loop system which does not use a heat exchanger. Or another example, a system may be a passive, closed loop system which does use a heat exchanger. Some systems are much easier to make than others and people with a basic knowledge of tools and construction can easily make a functional system. If one desires to make their own system, this variability in complexity would influence what type of system is chosen.

Cost is another factor and each system configuration comes with a variety of different cost and benefits. The costs of any specific system can vary widely from country to country and region to region. Certain configurations using certain types of equipment are more efficient than others in specific situations. The following information gives an in depth look at these various ways of constructing hot water solar collectors.

Different types of collectors are also shown at the the end of this page as well as examples of different common solar hot water systems.

This page describes the various systems that are being used to heat up water with the sun. For a more general description of solar hot water visit the Solar hot water page.

Simple systems[edit | edit source]

A very simple solar shower, effective in sunny regions, uses a black bag full of water hung in direct sunlight.

A very simple "system" can be devised by running water through some hose or pipe that is exposed to the sun, and connecting that to a storage vessel in a thermosiphon arrangement. A thermosiphon causes heated water to displace cooler water above it and as long as the heated water can continue upward, it will do so. The pipe/hose cannot have air present as this will halt the movement. There also needs to be a minimum of a ~4ft (1.2m) rise from hose to storage vessel. A loop can set up to circulate water from vessel to hose and back, which continues the heating process. Cool water is drawn from the bottom, circulated through the hose, and returns near the top of the vessel. As long as the siphon is not broken (air present), water can be dipped or drained out of the vessel for use. This is a simple open-loop system, meaning water enters and is removed for use from the system.

Another type can be called a batch heater, since it heats a volume of water using a thermosiphon, but uses a constructed solar collector to absorb the sun energy. Its limitation is that the tank is above the collector, which is on the roof or area exposed to the sun, so the hot water must be piped to the point of use, which costs heat loss. A special Communal solar water heating system has also been proposed using a batch heater.

More sophisticated systems[edit | edit source]

More sophisticated systems exist, some still employ an open-loop system (by tapping into an existing water heater or some other vessel). A solar collector in the sunlight with a pump and power source operate to either assist or supplant the existing water heating apparatus. The water circulates from the water heater tank to the exposed collector, and back to the tank, and this will continue to recirculate the water and heat it. A photovoltaic-powered low-volume circulating pump can be used in this system, avoiding the need for external electrical power. The more efficient, the larger the collector and the smaller the volume of tank storage, the faster the water will heat. The longer it operates, the hotter the water will become, until heat loss levels off the water temperature. This open-loop system works very well in climates where freezing temperatures are absent or rare. They can work in cooler climates using a system with drains to empty the water from the portion of the system subject to freezing. The drains can be manually operated or automatically thermostatically controlled. This type of system can be widely used to assist or supplant existing conventional water heaters.

Closed-loop systems are best in climates which freeze and reach lower temperatures, but are more sophisticated and therefore more expensive. In the closed-loop system a coolant, usually propylene glycol, is circulated through the collector then to a heat exchanger, where the heat absorbed is transferred from coolant to water. The propylene glycol remains liquid at much lower temperatures and will continue to absorb heat and transfer it to the water. The propylene glycol also remains in the system, hence the "closed-loop" name. The heat exchanger is either external to an existing water heater tank, or replaces the existing tank. A PV-powered low-volume circulating pump can also be used in this system.

These systems and associated technologies are arranged basically in order of cost, sophistication, and energy. The simple systems are certainly "appropriate technologies" and could be used with minimal investment, and with guidance, can be used by practically any culture, regardless of perceived sophistication. The open-loop systems can be used in developing societies in original construction or retrofitted, and as with the simple systems, the types of installation can greatly reduce energy costs, GHG, and allow greater focus on other needs. The closed-loop systems are more expensive, therefore more restricted to wealthier cultures, but their benefits are similar to the others. Based on per capita energy use, the more expensive systems can probably reduce more fossil fuel use than the others.

Modern mass-produced evacuated tubesW collect heat even below freezing. The tubes themselves are best suited for mass-production, but the rest of the system is more flexible in its manufacture. Evacuated tubes use a vacuum sealed space to separate the collector tube from the outside elements. When solar radiation is absorbed by these collectors and converted to heat, the vacuum barrier prevents most of this energy from escaping. Essentially, this method operates in a similar manner to a thermos. The ability to contain captured solar radiation while preventing loss to the outside environment is what allows evacuated tube systems to continually heat water, even if the temperature outside of the system is frigid.

Solar hot water pools[edit | edit source]

Energy derived from the sun drives and sustains life on earth. So why can't it heat your pool?

Swimming pools... your skin tingles in anticipation of diving in clear cool water on those ridiculously-roastingly hot summer days. This precise moment of contact makes all the hassle of cleaning and caring for your pool worth it, does it not? Now if only the scorching days lingered longer so you could laze a bit more in your backyard tropical-wannabe paradise. Alas, the seasons don't listen to you, and inevitably fall, winter and spring attack your precious pool, chilling it to its tiled bones, making it completely unusable to you. Much of the year your pool sits, unused and unloved, like a dog eagerly awaiting the return of its owner, like a dormant daffodil bulb waiting for the snow melt, like a ... Just as surely as we weren't sent here to Earth to suffer, surely we can all get what we want. And if for you that includes a heated pool without the financial and environmental expenses of fossil fuels, then welcome to the wide world of solar hot water systems.

Related projects[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Solar Spectra: Standard Air Mass Zero NREL Renewable Resource Data Center

- ↑ Earth Radiation Budget NASA Langley Research Center

- ↑ Solar Maps NREL: Dynamic Maps, GIS Data, and Analysis Tools

- ↑ us_pv_annual_may2004.jpg National Renewable Energy Laboratory, US

- ↑ Homepage International Energy Agency

- ↑ Liepert, B. G. (2002-05-02) Observed Reductions in Surface Solar Radiation in the United States and Worldwide from 1961 to 1990 GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH LETTERS, VOL. 29, NO. 10, 1421

See also[edit | edit source]

- Green tuning of space heating systems: besides heating water for using it as is, it can also be used for circulating it through radiators, in affect making a space heating system (see also: Heat pump system#Fitting a heat pump system to a house in practice)

- DIY solar thermal collectors

External links[edit | edit source]

Full Text Thesis[edit | edit source]

- Experimental Analysis of an Indirect Solar Assisted Heat Pump for Domestic Water Heating by BRIDGEMAN, A.G.

- Evaluation of a Stratified Multi-tank Thermal Storage for Solar Heating Applications by Cruickshank, C.

- Central Solar Heating Plants with Seasonal Storage for Residential Applications in Canada: A Case Study of the Drake Landing Solar Community by Wamboldt, J.