This page provides information on the Forbes Complex cogeneration unit connected to the Joseph M. Forbes Physical Education Complex, located on the Cal Poly Humboldt, HSU, campus in Arcata California.

Background[edit | edit source]

Forbes Complex[edit | edit source]

The Forbes Complex, Figure 2, was first built in 1973. The building was originally constructed to produce coaches and PE teachers. 30 years have passed since the construction of the Forbes Complex, and priorities have changed since the 70's. The Forbes Complex needed to be remodeled to meet new concerns such as the need for new types of physical education, and to reduce energy consumption levels in the Forbes Complex.

Cogeneration[edit | edit source]

Cogeneration (also combined heat and power or CHP), is the process of producing electricity as well as useful heat energy. This useful heat energy is often a steam byproduct from an engine and can be used as a form of heating for domestic or industrial purposes, such as heating water. There are three main types of CHP production: large, mini, and micro. Large CHP production is mainly used in factories or large energy producing settings such as Figure 3. Most large scale CHP use is in other locations like Denmark and Scandinavian countries. Mini and micro CHP are defined by their energy production. MicroCHP usually produces 5 kWe (kilowatt of electricity) or less and is used in houses or small businesses. MiniCHP produces between 5 kWe and 500 kWe and is used in institutions and large businesses. The Forbes Complex cogeneration unit is larger than a miniCHP system and could be considered a larger scale application but is very close to the miniCHP bracket.[1]

Decentralization paradigm[edit | edit source]

HSU's cogeneration system, and most small scale cogeneration systems, are examples of decentralized energy (also distributed power or distributed generation): the generation of energy from several smaller plants rather than a single conventional power plant. Typically these plants are on-site or otherwise near the population being served. With the ability to tailor a system to local energy habits combined with a reduction in line losses, decentralized systems can achieve higher efficiencies.

Forbes Complex retrofit[edit | edit source]

Overview[edit | edit source]

The retrofit of the Forbes Complex was aimed at rejuvenating the aging building. The project renovated roughly 200,000 square feet of obsolete classrooms. To address serious health and safety problems, the project upgraded building systems and fixed deferred maintenance problems. The project also addressed Title IX problems by redistributing space for gender equality. Another upgrade was the installation of the HSU Forbes Complex cogeneration system.[2]

Cogeneration design and installation[edit | edit source]

The designs for the cogeneration system commenced in September 2003 by DTE Energy, and the installation of the Energy/Now ENI 830 cogeneration unit commenced in November of 2003. From information gathered the cogeneration system was completed in July of 2004[3] and was installed by NORESCO as shown in Figure 1.The system has not been completely functional since its installment because when designing the system, DTE did not follow the engine manufacturers recommendations, which has caused most of the problems.

Project cost[edit | edit source]

The total project was estimated at $4.8 million in February of 2004, which included the other energy saving installments. Most of the cost was to be paid for through incentives from PG&E or made up for in energy savings from PG&E.[4] A document obtained from PG&E states that the Forbes Complex cogeneration project had "total eligible costs" of $2,985,795.[5]Enforcing the idea that project was paid for by a third party, the HSU Facilities Management site states that the total project cost was $4,808.

Forbes cogeneration cycle[edit | edit source]

The Forbes Complex cogeneration system uses a reciprocating internal combustion engine. As previously mentioned the system is close in size to the miniCHP classification and provides heat for the pool, Forbes Complex building, Kinesiology Athletics building, Science A,B,C,D and Wildlife buildings.[6]

Step 1: Combustion of natural gas[edit | edit source]

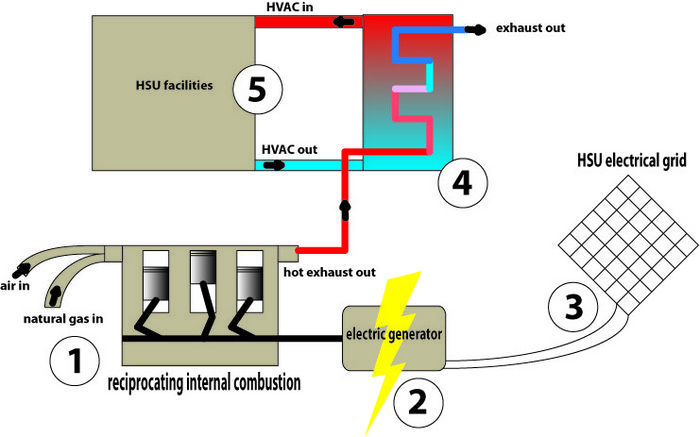

The reciprocating internal combustion engine in step (1) of Figure 4 uses natural gas as its fuel source. Natural gas is commonly used in the United States for heating and energy production. Natural gas varies in composition but is mainly composed of methane, typically 85%. Other gases include: nitrogen, butane, propane, ethane, and helium.[7]

The general equation for complete combustion of methane is:

Reciprocating internal combustion engines use cylinders, much like a car, to take expanding gas from combustion and create mechanical energy, in the form of shaft rotation. As seen in step (1) of Figure 4, air and natural gas enter the combustion chamber, gas is then combusted resulting in mechanical energy and hot flue gas (carbon dioxide, water, and heat as seen in the above equation).

Steps 2 and 3: Conversion of mechanical energy to electrical energy and distribution to grid[edit | edit source]

In order to convert the mechanical energy produced in step (1) of Figure 4 into electrical energy an electric generator is used, step (2) of Figure 4. After conversion the resulting voltage is too low for transmission. A transformer, Figure 5, increases the voltage which then allows electricity be distributed to the grid, step (3).

Steps 4 and 5: Heat exchange and distribution to campus facilities[edit | edit source]

Heat can be recovered from hot flue gas in step (1) of Figure 4 via use of a heat exchanger. Heat exchangers exchange heat between fluids. In the case of the Forbes Complex the fluids are air and water. In step (4) of Figure 4 hot flue gas travels through a pipe network allowing heat to be transferred to water which can then be circulated through the heating and ventilation system (HVAC) of campus facilities, step (5) of Figure 4.

Amount of electricity produced[edit | edit source]

In 2006 and 2007 HSU consumed 10 million kW-hr of energy.[9] This is an average energy consumption of 1,141 kW or at peak times about 2,800 kW. When in operation the system produces roughly 750 kW of power, electricity is tied to the HSU grid. Another cogeneration unit on campus, the HSU dorm cogeneration unit, produces roughly 10% of HSU's energy.[4] During peak times the Forbes Complex could produce roughly 27% of HSU's power. The cogeneration unit is capable of producing 100% of the heat for the Forbes Complex heating requirements.

Current status[edit | edit source]

Forbes Complex cogeneration is currently partially operational. Several breakdowns and inefficiencies in the system have occurred. According to HSU Facilities Management staff, the problems stem from the system design. DTE Energy did not follow design specifications of the engine manufacturer. Facilities Management believes the next round of repairs will make the plant dependable.

Engineering students in Cal Poly Humboldt's Department of Environmental Resources Engineering are performing the second phase of studies that investigate a fuel cell system as a replacement for the Forbes Complex cogeneration unit.

The first phase of the project was performed in Solar Thermal Engineering (ENGR 477, Fall 2013). The engineering students performed feasibility analyses to determine which fuel cell technology would be physically and economically viable. Four fuel cell technologies were considered in these studies: solid oxide, molten carbonate, phosphoric acid, and proton exchange membrane. The results of the studies indicated that the solid oxide and phosphoric acid fuel cell systems would be viable replacements for the existing cogeneration unit. Whereas the molten carbonate and proton exchange membrane technologies were not recommended for use on campus based on size and cost. The only available molten carbonate system is 5 times larger than the existing system and would not fit at the current site. Further, it would be too costly to implement and did not return a net savings by the end of its design life. The proton exchange membrane system would only be viable as a peaking plant, but it was also found to be too large for the existing site. Thus, the solid oxide and phosphoric acid fuel cell systems were recommended for further study.

The second phase of the project is currently underway in Capstone (ENGR 492, Fall 2014). The engineering students are performing a siting assessment and economic analysis to determine which of the two fuel cell technologies should be implemented and how they would incorporate the system into the existing cogeneration heating infrastructure.

Related information[edit | edit source]

External links[edit | edit source]

- Forbes Complex

- Cal Poly Humboldt

- NORESCO

- Wikipedia: Co-generation

- HSU Facilities Management: Forbes project page

- DTE Energy

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Cogeneration.(n.d.). In Wikipedia. Retrieved December 11, 2009, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cogeneration

- ↑ Physical Education Project (PEP) Project Objectives. (2007, March 8). Retrieved December 11, 2009, from HSU Facilities Management website: http://web.archive.org/web/20080720140852/http://www.humboldt.edu/%7efacsmgmt/PEP/PhaseII.html

- ↑ HSU Completed Projects. (2007, January 4). Retrieved December 11, 2009, from HSU Facilities Management website: http://web.archive.org/web/20090123222853/http://humboldt.edu:80/~facsmgmt/projects/EnergyConservation/EnergyConserv.html

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Kozel, T. (2004). Cogeneration Plant to Provide Electricity and Heat for Humbolt State University. District Energy Now, 19, 4. Retrieved from http://web.archive.org/web/20070221211359/http://www.districtenergy.org:80/pdfs/04WinterNewsletter.pdf

- ↑ PG&E Self-Generation Incentive Program. (November 2005). Retrieved December 11, 2009

- ↑ Personal Interview: Tim Moxon Senior Director of Facilities Management at HSU. Personal Communication. 11/17/09

- ↑ Natural Gas.(n.d.).In Wikipedia.Retrieved December 11, 2009,from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Natural_gas

- ↑ Combustion.(n.d.).In Wikipedia. Retrieved December 11, 2009, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Combustion

- ↑ HSU Energy Facts and Figures. (n.d.). Retrieved December 11, 2009, from Green Campus Program at HSU website: http://web.archive.org/web/20090609172804/http://www.humboldt.edu:80/~greenhsu/cms/gc/main/hsu-energy-stats